Water Temples in Bali: Merging Religion and Science

Peter Prevos |

1740 words | 9 minutes

Share this content

Winter in southern Australia is a time to escape to more tropical locations to soak up some sun. In 2014, we decided to spend a week in Bali, the most popular tourist destination in the Southern hemisphere. Even though this was a holiday, I could not resist taking a bike ride through the sawahs to view works of Dutch colonial water engineering and the famous water temples in Bali.

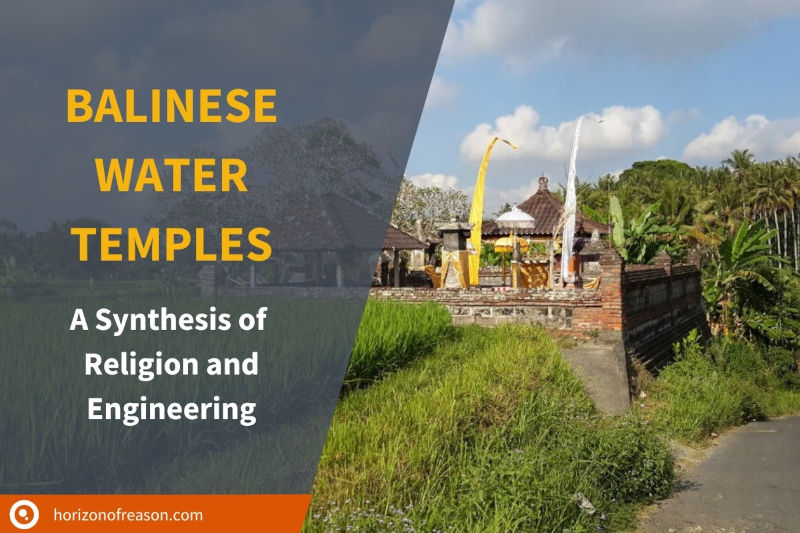

Water temples provide a fascinating insight into how farmers combine religion and engineering to manage water. This article discusses how the Balinese synthesise rational engineering and the social and spiritual dimensions of water to optimise their rice harvests. This article is based mainly on the work by American anthropologist Stephen Lansing who has studied Balinese irrigation systems for many decades.

Water Temples in Bali

Bali is famous around the world for its magnificent green sawahs that cling to the steep hills. Farmers irrigate rice paddies through a terraced system of faceted paddocks. An intricate network of channels that originates from springs and lakes in the volcanic mountain range in the centre of the island. The water slowly makes its way from the highlands to the ocean, irrigating the fields on its path down the slopes. This complex irrigation system has existed for many centuries. The Dutch colonial engineers were impressed by the achievements of the Balinese. What these temporary overlords did not realise was that this intricate system for water management was not merely a triumph of rational engineering an organically organised complex system for managing natural resources.

The primary organising units of the Balinese irrigation system are the subaks. These are religious and social organisations that coordinate everything related to the cultivation of rice, including irrigation. The subak system developed over many centuries, continually evolving over the past thousand years to accommodate new circumstances. In 2012, the cultural landscape of Bali was given World Heritage status by UNESCO in recognition of its unique integration of religion, farming and ecology.

A Subak is a collective of farmers within an irrigation district that congregate around Balinese water temples. The subaks are democratic organisations where farmers and the priests discuss their irrigation strategy. The water temples are organised in the same way as the rivers and irrigation channels branch out from the head of the catchment.

The primary water temple is the Pura Ulun Danu Batur, located along the rim of the crater of Lake Batur in the Balinese mountains. From this upstream temple cascades a network of regional water temples, each controlling a section of the irrigation system. The Ulun Suwi (Head of the Terraces) temples coordinate irrigation for a group of subaks. Most subaks have a Ulun Carik (Head of the fields) temple where farmers perform rituals and hold meetings to manage the systems.

Each framer also their Bedugul, a shrine at the place where the water first enters his fields. This hierarchical system of temples ensures that decisions about water are made at strategic points in the system. The regular rituals accompany the water with blessings and offerings from the head of the catchment, down to the place where it is converted to rice.

Combining rational water management with religion makes the Balinese irrigation system unique. Such a combination seems contradictory in a world that is dominated by scientific thinking.

That the traditional system is effective became apparent when in the Indonesian government decided to implement a Green Revolution in the 1970s. This revolution introduced scientific thinking to agriculture in Indonesia. This policy reduced the role of the Balinese water temples, which were invisible to the consultants that advised the government. This well-intended policy disturbed the delicate balance developed over the centuries. With the introduction of scientific farming, pests returned, and rice yields plummeted. The Indonesian government recognised these problems rescinded the orders to use specific seeds and chemicals in 1988, allowing farmers to return to their old practices.

The religious dimension of this system is in direct competition with the scientific mindset of water managers. The remainder of this article shows how religion and engineering are not necessarily diametrically opposed. Both dimensions of the human experience collaborate to manage the Balinese irrigation system.

Religion and water

Balinese irrigation is strongly interlinked with the island’s natural environment, both at a material and at a spiritual level. Religion plays an influential role in the management of Balinese water. The religious aspects are mediated through the network of water temples and priests.

Subak members collaborate to decide on water allocations and the timing of water supply, supported by rituals mediated by priests. The performance of these rituals is of critical importance in Balinese water management. The system does not rely on divine intervention, but the rituals create a strong sense of collective purpose. The water rituals are closely linked to observations of the natural environment and managed through a complex calendar system.

The word ritual is often used in a negative sense. A ritual is, however, not necessarily a repetitive activity undertaken for no reason. A well-performed ceremony is a means to connect the sacred with the profane. The performance of ritual sacralises the natural environment, lifting it beyond the status of a resource exploited to maximise return to one with intrinsic meaning. On a more practical level, the structure of ritual often contains practical knowledge that helps the locals to optimise their decisions. This knowledge is developed over millennia of observation and trial and error.

The most crucial decision that farmers need to make each year is when to plant rice. Flooding the paddocks alters the chemical and biological properties of the soil, and the success of irrigation depends on the accurate judgement of the seasonal flow of rivers and springs.

Rice has to be irrigated at the right time to maximise yield. The ritual calendar determines the timing of planting. The timing of the nyunsung ceremony is the most critical moments in the farming calendar as it signifies the start of the planting season. Selecting the right time optimises the plant’s need for rainfall and sunshine, the harvest occurs in the dry time and pest minimises pest populations.

The key to Balinese water management is the way they measure time. The Balinese calendar is a complex interaction between two different ways to measure the passage of time. The first is uku, a 210-day calendar, independent of astronomical events. It is not a coincidence that the length of this calendar is the same as the growth cycle for Balinese rice. The second calendar follows the lunar phases, which means that a particular month does not always start on the same solar day. To optimise the date for planting rice, the temple priest decides the timing. In some places, the ideal day is marked by the appearance of a particular moss on an old tree, or by the presence of a type of grass, or the colour of the sea.

The knowledge required to manage the Balinese irrigation system is embedded in the Hindu mythology of the island. A myth is not necessarily a story that is factually not true. Mythology has several levels of interpretation. On the surface, mythological stories are fictional and irrational accounts of gods and the supernatural. Below this superficial view, myth contains practical and philosophical knowledge obtained through centuries of experience with the land.

The contemporary scientific approach to managing a complex system the Balinese irrigation would be to deploy thousands of sensors around the island and crunch the numbers using sophisticated computer models. This approach is, however, not much different from how the Balinese system has evolved. Over the centuries, farmers and priests have observed nature and how this impacts their farming. The mythological system has no underlying theory, but knowledge emerges from the long-term observations and is wrapped in narrative instead of formulas.

That the Balinese system leads to optimised results was shown by Lansing and Kremer who developed a computer model of the system. The model simulates the behaviour of farmers to see how such a system evolves. When the model starts with a random pattern, it develops over time to a situation that closely resembles the Balinese system. This model shows how religious doctrine can contain proto-scientific information that leads to an optimised model.

Water Engineering and the Horizon of Reason

We can extract scientific knowledge from the Balinese religious system but what about the religious dimension itself? This article is not making any claims about the ontological validity of the supernatural claims in Balinese Hinduism. Whether or not the Balinese water goddess Dewi Danu exists is an irrelevant point.

Religious symbolism and mythology is a vehicle to convey traditional knowledge about the local environment. The religious traditions in Bali have evolved over the centuries to develop a coherent system to manage natural resources eventually. The spiritual dimension not only contains practical knowledge, but it also is the social structure that enables farmers to cooperate consistently and rationally through the hierarchical system of temples. Furthermore, the spiritual dimension of Balinese water management ensures that the resource has intrinsic value, beyond its utilitarian purpose to grow rice.

The Balinese Subak system is a living example how a decentralised water management approach can be instrumental in avoiding a Tragedy of the Commons, as described by Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom. Managing a natural resource without any coordination from above will leads its depletion. Economists traditionally believe that the 'invisible hand' will guide us if everybody maximises their self-interest. Ostrom showed that this approach is not suitable for natural resources. When users collectively manage natural resources, they establish rules over time that sustainably controls their resources, both economically and ecologically. In Bali, the subak system optimises the use of the land and water. Perhaps we could say that the Balinese water goddess is the invisible hand that guides the self-interest of the farmers.

Combining local religion with engineering places Balinese water management on the Horizon of Reason. The Balinese water temples illustrate how managing water is more than a volume of H2O controlled by engineering. Water has an inherent social dimension that water managers should not ignore. Engineers often express water in cubic meters and milligrams per litre. For the people using the water, it has a much richer meaning that goes far beyond what we can express in numbers.

Share this content