Difference Between Male and Female Body Image Statistics

Peter Prevos |

2219 words | 11 minutes

Share this content

This analysis of body image statistics investigates the difference between male and female body image for men and women of different ages and reviews two hypotheses. The first hypothesis is that the ideal body image for women is that their ideal body shape is thinner than their perceived actual shape.

The most important indication of beauty for women, and to a lesser extent for men, is the prevailing ideal of thinness. The models on catwalks and in magazines portray unrealistic images that redefine the expectations that young men and women have of themselves. The result of this onslaught of idealised body shapes is that many women and some desire an unattainable and even unhealthy thin body (Lamb et al. 1993).

The power of marketing is that we don't buy things for what they do, but because of the kind of person we think it makes us. The first law of consumer behaviour states is that your real self, plus a product equals your perceived self.

This study measures the current and ideal body shape and the body shape of the most attractive other sex. The results confirm previous research which found that body dissatisfaction for females is significantly higher than for men. The research also found a mild positive correlation between age and ideal body shape for women. Older women are less concerned about being skinny than younger ones. For men, their age and the female body shape they found most attractive also correlated positively.

Perceptions of Beauty

This preoccupation with thinness is a recent development. The perception of women's body shapes has significantly changed over the past decades. In the early 1940s, thin people with ectomorph bodies were perceived as nervous, submissive and socially withdrawn. By the late 1980s, this perception had changed, and thin people were the most sexually appealing (Turner et al., 1997).

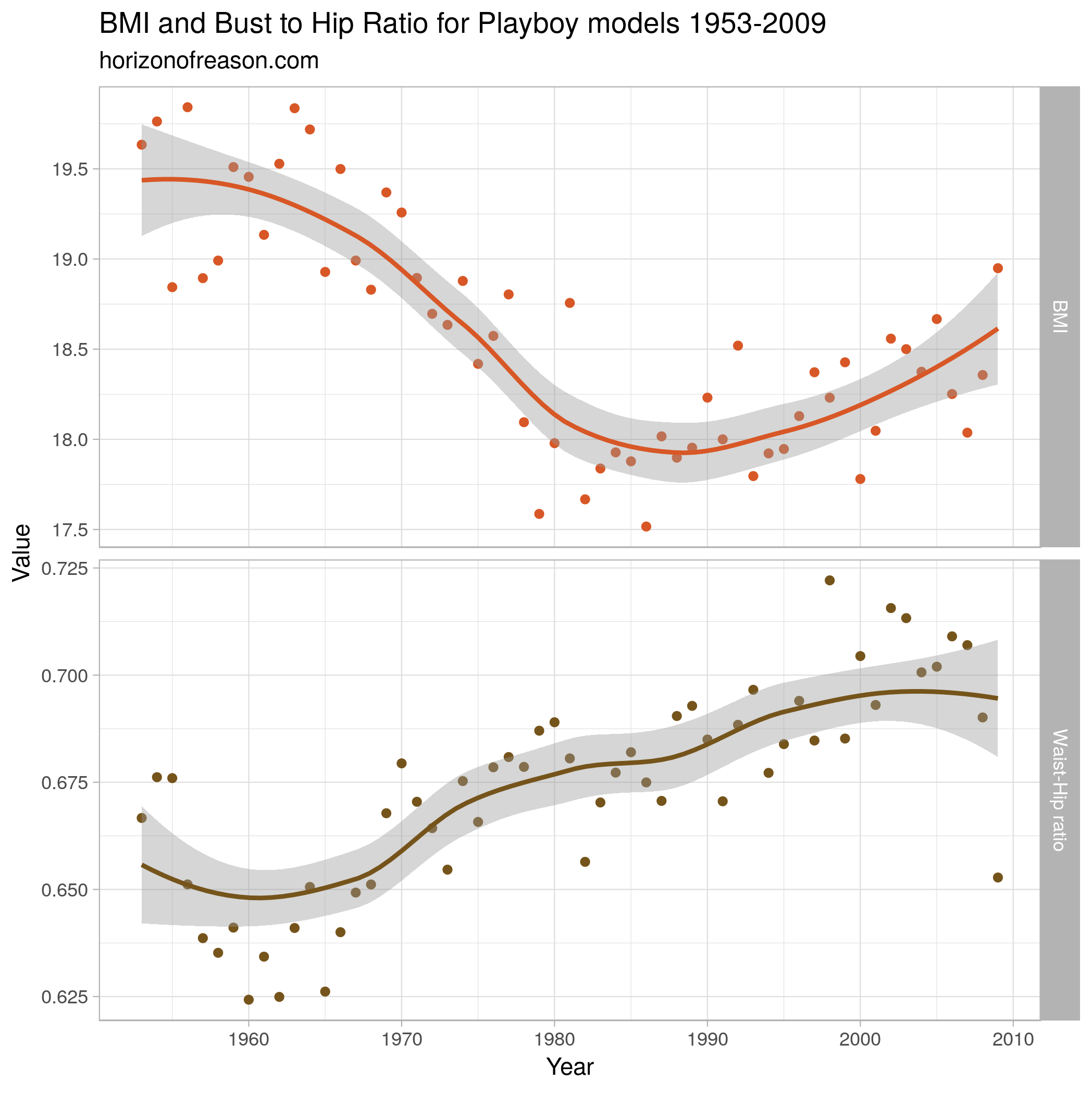

Several researchers have found that the female body depicted in the media has become increasingly thin. Bust and hip measurements of centrefold models show that between 1960 and 1979 there was a trend towards non-curvaceousness of women. This trend was, however, reversed in the early 1990s (Garner et al., 1980; Turner et al., 1997; Sypeck et al., 2006; Wiseman et al. 1992).

The Body-Mass-Index (BMI) of Playmates shows a steep decline from the 1950s to the 1990s and has slowly crawled back. The current index of around 19 kg/m² is at the lower edge of healthy weight. The waist-to-hip ratio has gradually increased from the first publications until recently (Figure 1). The higher this ratio, the less curvaceous a woman is. You can download the data and the analytical code from GitHub.

Body Dissatisfaction

Parallel to the decrease of the ideal body shape for women, the dissatisfaction that women have with their body shape increased (Cash et al., 2004. In recent years, some researchers have found that females are more likely to judge themselves as overweight than males. This tendency was most active in adolescent and young adult women (Fallon and Rozin, 1985 Tiggeman and Penningto 1990; Tiggeman, 1992).

Concerns with body image have been linked to a decrease in self-esteem and an increase in dieting among young women (Hill and Rogers, 1992). This increase in dieting among young women indicates the onset of eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Barker and Galambos, 2003; Fear et al., 1996; Lamb et al., 1993).

Numerous researchers have studied body dissatisfaction in recent years (Abel & Richards, 1996; Byrne & Hills, 1996; Cash et al., 2004; Fallon & Rozin, 1985; Fear et al., 1996; Lamb et al., 1993; Tiggeman & Pennington, 1990; Tiggeman, 1992). In this study replicates the findings of Fallon and Rozin. They concluded that 33% of men and 70% of women rate their current figure as larger than ideal and that body dissatisfaction among women is much larger than for men. Fallon and Rozin also found that men judge the female figure they found most attractive as heavier than women's ratings of the ideal body shape.

Hypotheses

The first hypothesis tested in this study is that the ideal body shape for women ($ideal$) is thinner than their current self-assessed body image ($current$) and the perfect body shape for men is heavier than their current body shape.

$$H_{1w} : ideal - current < 0$$

$$H_{1m} : ideal - current > 0$$

Some research has been undertaken to determine generational differences in body shape preferences (Lamb et al., 1993). Tiggeman and Pennington (1990) researched body size dissatisfaction for children, adolescents and adults and found significant differences between the age groups.

It should be noted that they used different types of body image scales for each age group. Lamb et al. (1993) compared two generations and found significance in gender and cohort differences. These cohort differences confirm the recent increase in body dissatisfaction and eating disorders among mainly young women. In this study, the ideal image for females of different ages and the most attractive female body shape, as judged by men, will be determined for various age groups. The second hypothesis of this study is that there is a positive correlation between age and the ideal figure for females and between age and the female body image that men find most attractive.

$$H_2:R_{ideal,age} >0$$

Body Image Experiment Method

Participants

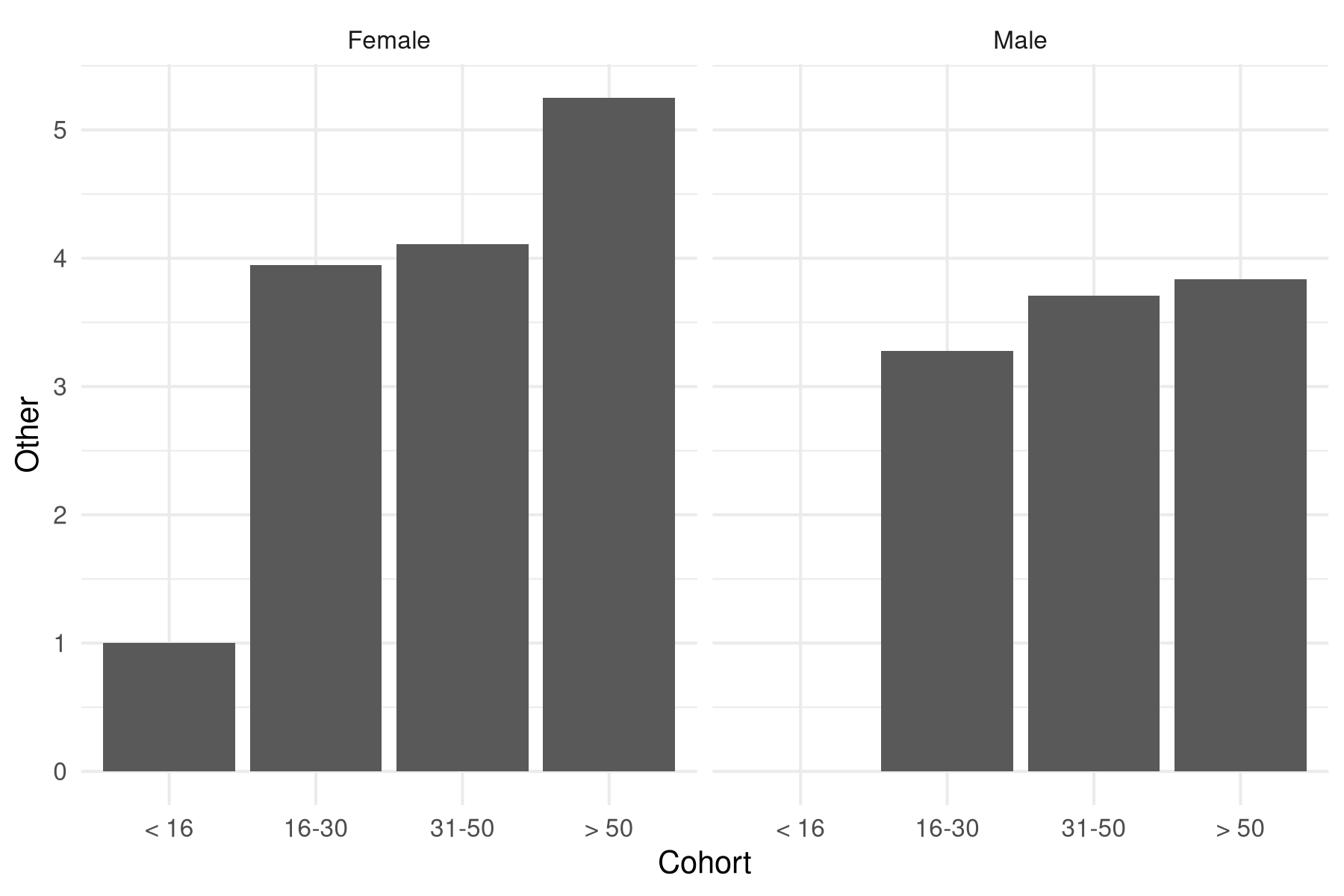

The participants of the survey are unsolicited visitors to the Monash University website. Most participants were students undertaking the psychology course. No socioeconomic information is available. The survey data contains 166 surveys completed between 3 January 2003 and 6 March 2004. Of the respondents, 59 are male and 107 female. Fourteen surveys were only partially completed and were not considered in the analysis. Table 1 shows the age distribution over the full data set. The cohorts taken into account for this survey are men and women between 16 and 30 years of age.

| <16 | 31–50 | 16–30 | >50 | sum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1 | 46 | 56 | 4 | 107 |

| Male | 0 | 29 | 24 | 6 | 59 |

| Sum | 1 | 85 | 70 | 10 | 166 |

Materials

This body image experiment consisted of questionnaire with seven questions regarding body shape, age, gender and possible concerns regarding body shape and dieting. Question 1 (current body shape), 2 (ideal body shape) and question 6 (body shape of the other gender found most attractive) and the questions about gender and age of the online questionnaire were used for analysis. The remaining survey results have not been considered.

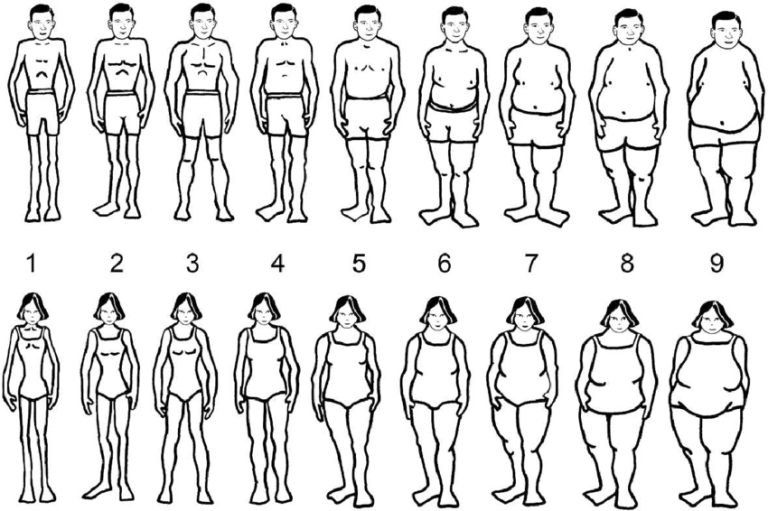

Participants compared a set of nine drawings, showing an increasing body size (Figure 2). Subjects scored the first seven questions between one and nine. This type of survey has been widely used in similar research regarding body dissatisfaction (Abel and Richards, 1996; Byrne and Hills, 1996; Fallon and Rozin, 1985; Fear et al., 1996; Hill and Rogers, 1992; Lamb et al., 1993; Tiggeman and Pennington, 1990; Tiggeman, 1992).

The independent variables for this experiment are the gender and age of the participants. The dependent variables under consideration are the current body shape (current) the ideal body shape ($ideal$) and the gender found most attractive ($other$).

Of the 16–30 cohort, the results consist of 29 men and 56 women. A random sample of 29 women and all responses submitted by men ensured symmetry in the data. The complete data set determine the correlations between age and ideal female figures for both men and women.

Body Image Statistics

Body Image

The arithmetic mean and standard deviation of the three questions under consideration are summarised in Table 2. The results have not been tested for statistical significance. The results show that for women, the average current figure is larger than the average ideal. The perceived current body shape for men is much closer to the ideal. The percentage of women that considered their current body shape larger than the ideal ($current − ideal > 0$) is 75.9%. Only 37.9% of men thought that their current body shape was larger than their ideal.

| $n$ | $current$ | $ideal$ | difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 29 | 3.93(1.19) | 3.03(0.94) | 0.9(0.86) |

| Male | 29 | 4.14(1.55) | 4.03(0.73) | 0.1(1.37) |

Attractiveness

The results of this body image experiment also show that the ideal body shape for women increases as the age of the participant’s increases. The data shows a mild positive correlation between ideal body shape and age ($r = 0.3$). The female body shape that men find most attractive also changes slightly as age increases ($r = 0.33$). The ideal female body shape found attractive by men is slightly larger than the female ideal for the cohorts between 16 and 50 years of age, but significantly lower for the group older than 51 (Figure 3).

Discussion

The body dissatisfaction value for women found in this survey confirms previous research conducted in this area and is very close to the figure found by Fallon (1985). There is thus no indication that the high body dissatisfaction among young women has been decreasing over the past twenty years. One of the reasons most often cited for this continuing body dissatisfaction among young women is the influence of the media.

The media often reply that they are merely reflecting the ideals of the current generation. Previous research has, however, shown that the press indeed plays a significant role in shaping, rather than reflecting, perceptions of the female body (Turner, 1997).

There seems to be a circularity that needs to be broken to decrease body dissatisfaction among young women and reduce the occurrence of eating disorders. The only group that can take the first step is the media and the fashion industry. It is, however, doubtful that this will happen, given the commercial interests at stake.

Research results

The results of this body image experiment indicate that men are also slightly dissatisfied with their body shape. The ideal body image of men is slightly larger than their current shape (Fallon, 1985; Tiggeman et al., 1992). There are, however, differences in age cohorts for men. Younger men were shown to display positive body dissatisfaction older men a negative body dissatisfaction.

If the outcomes of this survey regarding the body dissatisfaction of men are statistically significant, then there are two possible reasons for the difference in the results. The ideal body image for men could have decreased in the twelve years between this study and the most recent reference cited above. Another reason could be an increase in actual body size. The real body shape for men in this study is indeed slightly larger, and the ideal body shape for men is slightly slimmer than previously reported Lamb et al. (1993).

Different body shape scales should be used to measure body dissatisfaction for the various age groups (Byrne & Hills 1996). Results can change significantly, depending on the type of body scale used (Tiggeman 1992). To test the sensitivity of the results of this study, the age group of 16–30 were divided into 16–21 and 22–30 (Table 2). When looking at the date for these two sub-groups, the results change only slightly. The age groups used in this study are broad, and further refinement could be achieved by using different body image scales.

Only the first part of the first hypothesis for this study has thus been confirmed. Further research into body dissatisfaction among young men needs to be conducted to verify the increase in body dissatisfaction measured in this study.

Conclusions

Fallon (1985) theorised that the difference between ideal body shape for women and the female body shape found desirable by men exists because women are misinformed about the magnitude of thinness that men desire.

This misinformation is, according to Fallon, caused by the prevalence of thin women in the media. They seem to assume that a woman’s primary motivation for preferring thinner bodies is that they want to be attractive to men. This motivation is not necessarily the case, as the desire to be thinner could also be caused by peer pressure from other females. No conclusion can be drawn about the personal motives for wanting to be thinner from the results of this study, nor any of the other studies used for this study.

The results of this body image experiment show that the ideal body shape increases as women get older. The female body shape found ideal by men also increases with age. This result could support the hypothesis proposed by Fallon (1985) which suggests that being attractive to the other gender plays a lesser role in the lives of older women.

Another reason could be that images in the media are mainly of thin young women. The jump in ideal body shape for women over 51 years of age is significant. The body shape found ideal by men of the same age does, however, only increase slightly. One could theorise that, as women reach menopause, they relax their quest for the ideal thin body, while men only marginally relax their preferences.

This study has confirmed most of the findings of earlier research. Further research into male body dissatisfaction is required to verify the results of this study. Also, study into the motivation for young men and women to be thinner is needed to determine how this trend of increasing body dissatisfaction can be turned around.

Share this content