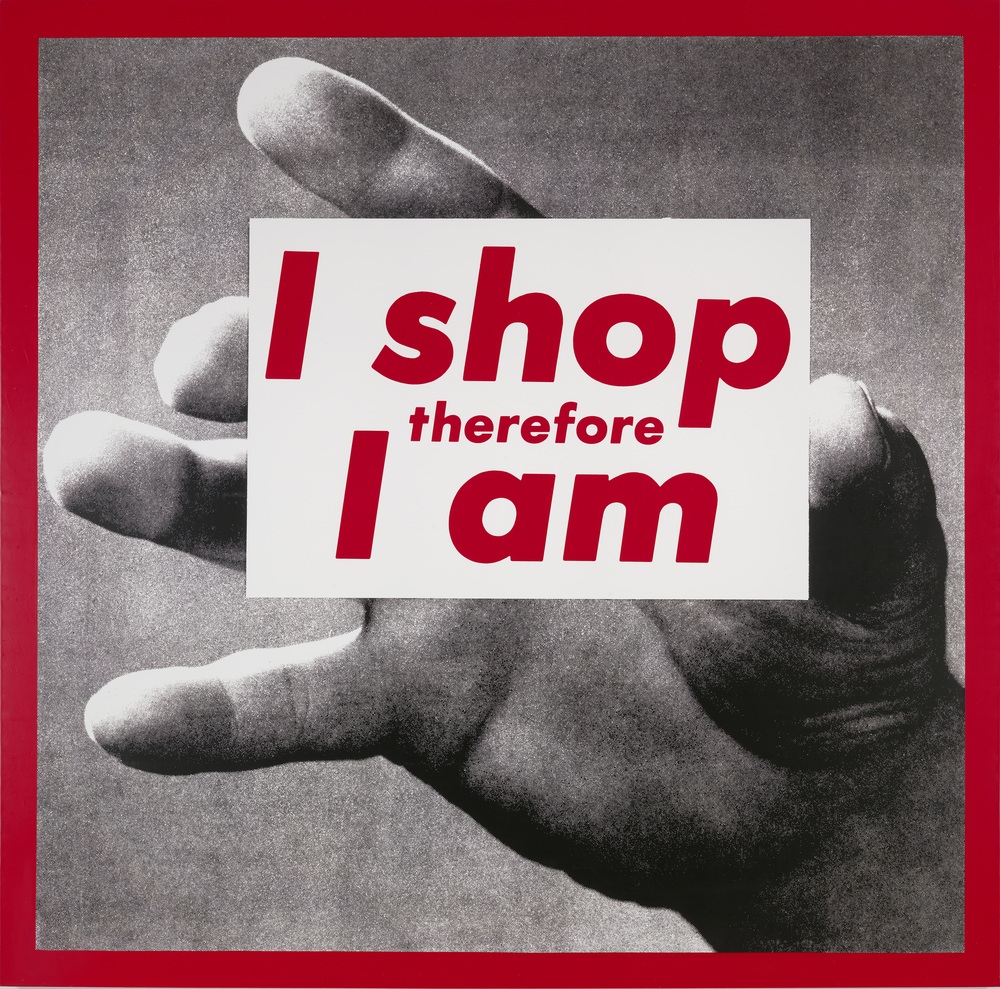

I Shop Therefore I Am: The First Law of Consumer Behaviour

Peter Prevos |

1487 words | 7 minutes

Share this content

Think about the last time you purchased a magazine. Did you perform a rational hedonistic calculus and compared the benefits of spending fifteen dollars on New Philosopher magazine, a lunch, or deposit the money into your savings account? Almost certainly, your choice to purchase New Philosopher was not based on a rational process where you compared the various options, but the result of rationality bounded by your psychology and social background. Perhaps you bought this magazine to casually place it on your coffee table to cultivate your public persona? The fact that you are reading this article suggests that your interest in philosophy is perhaps a bit more sincere than merely a means to impress your friends.

The reasons we buy stuff are complicated and are in most cases not the result of a rational decision process. Marketers and anthropologists understand that we don't purchase things for what they do for us but for what they mean to us. All purchases have a practical as well as a symbolic motivation. Your car is more than a hunk of metal that takes you to work and back. Clothes are more than a protective layer to compensate for our lack of body hair. The car we drive and the clothes we wear express our social identity, more saliently, they communicate the type of person we would like to be. Even consciously not caring about brands is effectively a sign of our personal preferences to the outside world.

Erving Goffman explained our purchase behaviour through a theatrical metaphor. He argued that our social interactions are guided by the roles we play in public life. To achieve the desired effect on others, we use a script through the actions we take and the language we speak. Our purchase behaviour sets the mise en scène for the performances that form the backbone of our public life. We purchase products to create the backdrop to our lives and to use them as props. This pattern is not unique to contemporary affluent societies but can also be found throughout histories and cultures.

The industrial revolution was a turning point in this behaviour. Our innate desire to own things to construct our ideal self, combined with our recently acquired unparalleled wealth has created a situation where environmental and social values are at risk. This growth has been driven by the science of marketing, which has developed profound insights and rhetorical methods to maximise sales.

First Law of Consumer Behaviour

Marketers have a deep understanding of our motivations to purchase the things we need and want. The ethical position in this debate often revolves around the notion that we don't need to buy the things we do, we merely want them. This statement presumes that we need a rational motivation for each purchase we make.

To understand how marketers think we have to reposition the concepts of needs and wants. When a child tells his mother that she needs a mobile phone, the swift response will often be: "You don't need a phone, you just want one". The common sense view of needs and wants assumes a normative hierarchy between the two concepts. A need is interpreted as a sine qua non, something without which your life would not be possible. A want is considered to be solely motivated by desire and contingent to living our lives. The parent faced with the choice to purchase a mobile phone for her child will more often than not rationalise her decision by justifying the want as a need. A phone becomes a need because parents interpret the device as a way to keep their child safe.

This perspective on needs and wants is problematic because the distinction between the two is highly dependent on personal interpretations to distinguish between something we need versus something we want. In the extreme, all we need to survive is air, water and food. We can extend this list by referring to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees access to food, clothing, housing and medical care. But where can we draw the line between needs and wants?

Marketers have a different concept of needs and wants which is not based on a normative hierarchy but anchored in psychology. A need is a state of felt deprivation, and a want is a need that can be satisfied with a purchase. Maslow's hierarchy of needs helps to explain this idea. Maslow stated that our needs not only include physiological needs and safety. The hierarchy of needs also recognises that we need social belonging, self-esteem and self-actualisation. Material culture plays an essential role in achieving all of these needs. My laptop satisfies several of my needs. Writing this essay is a way to actualise my inner self. My computer also fulfils an element of self-esteem through its high-end specifications and social belonging through my membership of online communities and communicating with distant friends.

These insights into our purchase behaviour help marketers to increase the likelihood that people buy their market offerings. Our purchase behaviour is unpredictable at an individual level but governed by patterns at a collective level.

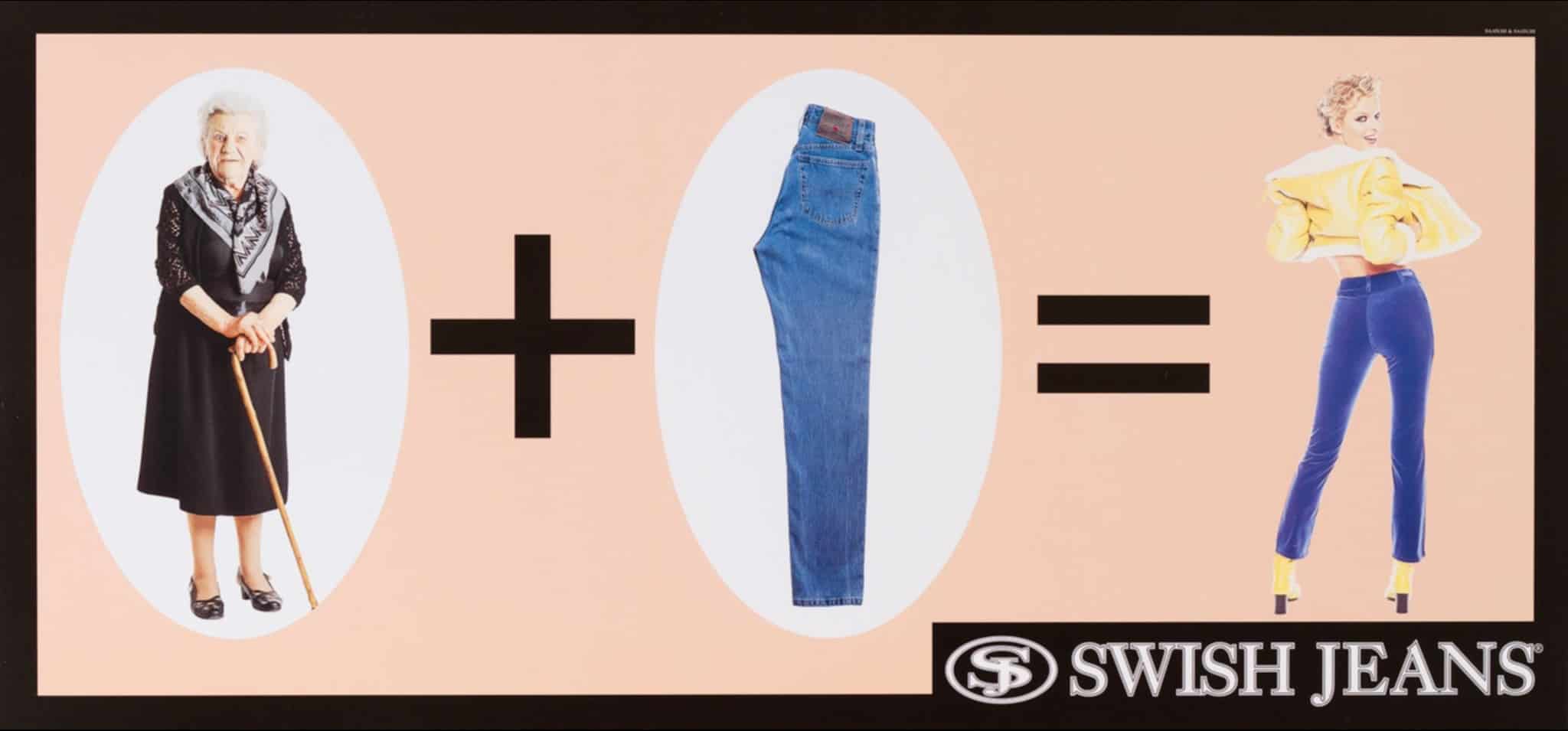

The real self, plus a product equals your perceived self

The first law of consumer behaviour states is that your real self, plus a product equals your perceived self. A magazine advertisement by fashion brand Swish Jeans humorously visualised this idea in 1996. The ad shows an image of an elderly lady, a plus sign, a pair of jeans, an equals sign, followed by fashion model Eva Herzigová. This add explicitly states the hidden message embedded in most advertising.

This principle permeates the majority of advertising and sales campaigns. Even promotion of unfashionable products such as toilet paper deploys images of harmonious families in immaculate houses. Advertising aims to create a Pavlovian association between the products they sell and the imagery of a perfect life.

We can rework this equation from a business perspective: the perceived self minus the real self, equals entrepreneurial opportunity. What this means in practice is that marketers can improve opportunities to sell products by increasing the promise of the perceived self. More controversially, advertising can also decrease perceptions of the real self to widen the gap between reality and our desired state of being.

Since the dawn of philosophy, thinkers have advocated that we should detach ourselves from the material world. In the European tradition, Socrates wandered through the Agora, telling his fellow Athenians that the search for wisdom is more important than material wealth. At the other bookend of the timeline of philosophy, we find the sharp critique of the Frankfurt School. Herbert Marcuse explicitly accused marketing of being the driving force of wasteful consumerism and the progenitor of false needs.

Marcuse seems to adhere to the common sense view of needs and wants, with its problematic and subjective differentiation between what is needed and what is merely desired. Removing the normative difference between needs and wants is enlightening because it better explains why we purchase products. That this explanation is valid is proven by the success of marketing, which applies this theoretical insight to maximise sales.

Removing the normative difference between needs and wants has significant ethical implications. It is not hard to see how this primary marketing mechanism can lead to unethical behaviour by marketers. Fashion advertising often portrays the unattainable ideals of female bodies, lowering the self-image of vulnerable women. These strategies have even been identified as contributing causes to eating disorders. The ongoing need to generate revenue results in a barrage of new products and advertising, which can lead to a level of consumption that damages the natural environment.

Promoting goods for sale is as old as commercial activity itself. The advent of marketing science has given salespeople profound insights into human behaviour. It could be argued that with the advent of social media, marketers know more about human behaviour than social scientists merely because they have unparalleled access to intimate details about our thoughts and behaviours. Contemporary marketing is much more sophisticated than anything ever seen in the history of humanity. Firms deploy advanced rhetorical strategies, supported by scientific research, that exploit our bounded rationality to maximise sales.

Many philosophers appeal to our inner self and call for detachment of the material in favour of the inner life. These philosophers ignore the significance of material possessions to our everyday lives. Their lofty ideals have little influence on our inherent need to purchase stuff to enact our social roles and construct our public persona.

This insight into the first law of consumer behaviour does not negate the ethical responsibility of marketers to protect vulnerable customers and prevent harm to the environment. With great power comes great responsibility, but the enormous forces of economic interest more often than not drown these ethical concerns.

Share this content