Pornography Art and the Commodification of Sexual Desire

Peter Prevos |

1674 words | 8 minutes

Share this content

Pornography is available in many different types of media, closely following the vanguard of modern technology. There is also a plethora of genres, each with varying degrees of explicitness. There is no consensus among scholars on a definition of pornography. Some consider nude photographs in Playboy magazine pornography; while on the other end of the spectrum, this label is reserved for explicit depictions of actual sex. This final essay discusses the special status of pornography art in contemporary society following Marxist, semiological and anthropological perspectives on material culture.

This essay focuses on so-called ‘hardcore’ pornography as depicted in films rated X-18+ by the Australian Office of Film and Literature Classification. These are productions containing “depictions of actual sexual intercourse and other sexual activity between consenting adults”.

Marx and Pornography

The Marxist view of material culture focuses on the people producing and consuming products, rather than on the objects of consumption themselves. A core aspect of Marxist theory is the idea that capitalism facilitates the commodification of the social world by disconnecting the producer from the consumer. Marx used the term commodity fetishism to describe the disconnection of products from the story of those who made them and how they were made, not to be confused with sexual fetishism, which is an erotic fascination with a specific object or part of the body.

This disconnection from the social environment of their production allows for products to become commodities and abstracted to mere exchange values. Marx argues that commodity fetishism is an unnatural and undesirable state because commodities not only hide but replace relationships between people.1 Producers and consumers having no direct social contact prevents the development of a moral connection between them.

In the case of pornography, commodification creates a disconnection between ethical and emotional aspects of the act of producing pornography from the act of consuming it. This issue is the foundation of early feminist pornography criticism by writers such as Andrea Dworkin and Catherine McKinnon, who focus on the examination of misogynistic sexual representations.2

Feminism and pornography

The feminist critique follows from the argument that pornography is based on unequal power relations between the men and women involved in its production. The argument continues, following Marx, by asserting that the commodification of pornography severs the link between production and consumption and thus neutralises any ethical issues related to its production; promoting similar behaviour by those who consume it. Pornography is isolated as the focus of concern with violence towards women and is as such often defined in its perceived ability to harm.

Experimental research to determine connections between viewing pornography and violent behaviour has, however, not found any conclusive evidence of a causal link between the two.3

Recent feminist discourse has been more positive towards pornography, giving rise to a polarised debate between anti-pornography and anti-censorship campaigners. Most research used to support anti-pornography claims has not considered the possibility that women may enjoy viewing sexually explicit material. Although many women assert to be anti-pornography and say they do not enjoy watching it, experimental research indicates that women do get aroused viewing pornographic films. It subsequently could be argued that the lack of sexual arousal in women watching pornography has been socially constructed.4

Semiology and Pornography

The Marxist approach does not seem to be able to provide a satisfactory account of pornography. Although commodity fetishism appears to be a valid objection against commodification in general, the feminist critique that watching pornography, disconnected from ethical concerns about its production, causes violent behaviour, has not been justified and simplifies the complexity of the semiological and cultural dimensions of pornography.

From a semiological perspective on material culture, the focus is moved away from the people involved in production and consumption, in favour of the objects themselves. Pornography is analysed as a text, not in its literal meaning as a text about sexuality (from the classical Greek: ‘writing about fornication’), but as an aspect of contemporary public discourse about sexuality. Baudrillard distinguishes different ways of looking at consumption: “an object is not an object of consumption unless it is released from its psychic determinations as a symbol; from its functional determinations as an instrument; from its commercial determinations as product; and is thus liberated as a sign …”.5 Pornography is, using the words of Roland Barthes, a ‘mythology’, that can be analysed to provide an insight into the society in which it is produced and consumed.6

Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto: I am human and I consider nothing human strange to me.

Terrence, The self-tormentor.

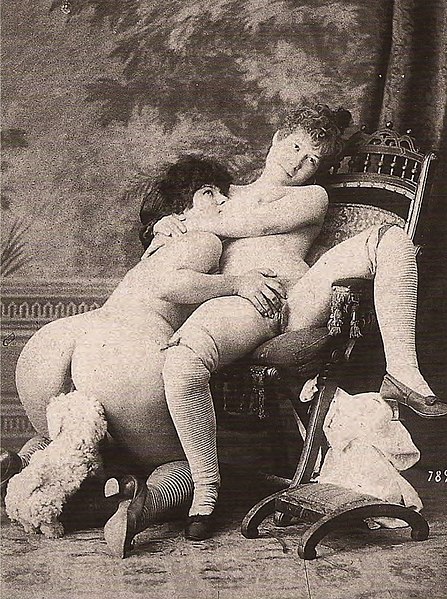

To entangle pornography’s place in contemporary society, it is required to look beyond the superficial moral and aesthetic aspects, usually associated with the subject. Pornography has existed for many centuries but has historically been restricted to underground distribution channels. Over the past decades, sexually-oriented material has become available in mainstream media and representations of sexual activity have become more explicit. The ‘pornofication’ of the cultural landscape and proliferation of hardcore pornography, propelled by mass media, can, however, not be explained away as a lapse of morals and cultural decay.7

The increased consumption of pornography is a sign of a reconsideration of traditional values. Western society, dominated by Judaeo-Christian thinking, traditionally values otherworldliness over the physical and temporal. Pornography is considered deviant from accepted social norms because of its emphasis on physical aspects of existence over metaphysical values.

Enlightenment thinking has, however, slowly eroded the influence of Christianity, leading to a reversal of the primacy of otherworldliness over the physical. In the wake of these changes, some have resorted to complete atheism and materialism. The pornographic literature of Marquis de Sade, for example, is laced with atheist philosophy. In more recent times, people are seeking to strike a balance between physical and spiritual values. Many shops dealing in metaphysical products, such as tarot cards, healing crystals and books about meditation, also sell products related to sexuality. This striving for a balance of the spiritual and the physical is also illustrated in the iconography of the exterior of Insight Adult Books.

The increased availability of pornography is thus a sign of changing value patterns in Western societies, which are moving ethical primacy away from the spiritual towards an appreciation of physical aspects of life. The disconnection of sexuality from procreation and a focus on hedonistic aspects has propelled it into mainstream culture, leading to democratisation and diversification of public sexual discourse.

The cultural significance of pornography can be explored by mapping the movement of pornographic expressions in society. The circulation of pornography in society is closely related to the available technologies. Until the invention of photography, expressions of sexual desire were limited to writing and painting. Recent technological developments in means of delivering media to consumers have substantially reduced the threshold for producing and obtaining pornography—visits to seedy sex shops in dark alleys are no longer required as the Internet delivers it directly into people’s houses. The adult retail industry has reacted to these changed attitudes to pornography by establishing more open and inviting places.

Pornography Art

The changed attitude towards representations of sexuality has faded boundaries between private and public discourse about sexuality. The fading boundaries affected definitions of art and pornography. The depiction of sexual desire has a long history in art, and many works that were controversial in their time are now accepted as art. Definitions of pornography and art have traditionally relied on categories such as ‘high’ or ‘low’ culture. Increased acceptance of pornography has, however, faded the distinctions between art and pornography.

An example of pornography becoming art is Made in Heaven, a series of works by American artist Jeff Koons, that consists of explicit photographs and statues of the artist with the Italian porn star and former member of parliament Ilona Staller. Historical developments in art points towards a greater acceptance of explicit depictions of sexuality and even the boundaries between hardcore pornography and what is accepted as art are fading.

The commodification of pornography stimulated the production of female-focused ‘erotica’, promoting the democratisation of sexual discourse. Sex shops, specialised in products for women, such as Myla and Taboobo have been established and also film producers produce pornography explicitly marketed to women.8 The fading of the boundaries between public and private sexual discourse and the availability of suitable technology has enabled many ‘amateurs’ to produce pornography, breaking down barriers between consumer and producer.

Until the development of cheap and powerful distribution methods, pornography has been limited to underground subculture. Marketing techniques used to sell pornography are aimed at deconstructing its ‘occult’ aspects by moving away from stereotypical gender-biased iconography, democratising public sexual discourse. Pornography has, however, not yet lost its deviant label and maintains a fringe position in society, providing a map of its fears and anxieties.

In this essay, it has been argued that Marxism is not able to provide a satisfactory account of pornography, mainly because it denies the real-world complexity of the issue. The semiological approach provides detachment from ethical constraints, showing porn to be a sign of changing value patterns in contemporary society. Analysis from the cultural perspective reveals an ongoing pornofication of the cultural landscape, fuelled by the changing value patterns. This brief essay illustrates how studying the place of pornography within contemporary society can provide valuable insights into its ethical boundaries and anxieties.

Notes

Marx, K. (1954). Capital. A critical analysis of capitalist production. Progress Publishers, Moscow.

Attwood, F. (2002). Reading porn: The paradigm shift in pornography research. Sexualities, 5(1):91–105.

Ciclitira, K. (2004). Pornography, women and feminism: Between pleasure and politics. Sexualities, 7(3):281–301.

Beggan, J.K. and Allison, S.T. (2003). Reflexivity in the pornographic films of Candida Royalle. Sexualities, 6:301–324.

Baudrillard, J. (1981). For a critique of the political economy of the sign. Telos Press.

Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies. Paladin, London.

Attwood, F. (2005). Fashion and passion: Marketing sex to women. Sexualities, 8(4):392–406.

Beggan, J.K. and Allison, S. T. (2003). Reflexivity in the pornographic films of Candida Royalle. Sexualities, 6:301–324.

Share this content