Anatomy of Sacred Space: The Joss House and Cathedral in Bendigo

Peter Prevos |

3333 words | 16 minutes

Share this content

Although there are seemingly irreconcilable differences between the various religions, they are all using the same building blocks. One of these building blocks is the concept of sacred space. This article analyses the Chinese Joss House and the Catholic Cathedral in Bendigo as sacred spaces to their respective religions. This article shows that even though both buildings serve very different traditions, the same basic principles apply to both places of worship.

Sacred Space

Sacred space is a significant social structure that reflects the symbols, beliefs and traditions of each religion tangibly and visibly. The holy or the transcendent is materialised in the sacred space by ritual acts and symbols.

Sacred space is a mediator for religious or sacred experiences. The iconography of the architecture and the objects in the building are the mediating elements. Sacred space is the ontological link between the transcendent and the immanent world. It is a manifestation of the transcendental world in the immanent world of the believers.

This link is maintained by the parallelism between the Macrocosm and the Microcosm. The unchanging reality of the sacred world is projected onto the ever-changing secular world in which the sacred space is built. Sacred space is externally and internally ordered by the traditional symbols of the respective religions.

The Chinese Joss House

The Chinese Joss House in Bendigo is the only remaining of four Chinese temples that were built during the gold rush in the middle of the nineteenth century. The Chinese name for the Joss House is ‘Big Gold Mountain Temple’, referring to the mining activities of the people that built it. After the gold rush ended, most Chinese went back to their homeland, and the Joss House was abandoned until 1972. In that year the Joss House came under the care of the National Trust. The Joss House currently serves a dual purpose. It is one of the prime tourist destinations in Bendigo and is also used for worship by the local Chinese community.

The architecture of the temple is basic; the Joss House is constructed of timber, and local hand made bricks, all painted in the traditional red colour. Chinese temples are usually decorated in auspicious colours, mostly red and gold. Grey and neutral colours are seldom used because they represent insignificance and unhappiness. Chinese temples are traditionally decorated on the exterior with sculptures of dragons, phoenixes, unicorns, tortoises, pearls, pagodas, fish and chimaera symbolising different virtues such as strength, longevity and material wealth. The Bendigo Joss House only has some basic ornamental work on the roof, and there is no indication that there ever have been any statues on the roof.

Geomancy — divination from signs of the earth — is a prime consideration in siting and planning of Chinese temples. Wheatley defines Chinese geomancy, also known as Feng Shui, as the analysis of morphological and spatial expressions of qi — the cosmic breath or energy — in the surface features of the earth. It is the art of adjusting the features of the cultural landscape to minimise negative influences and gain maximum advantage from favourable conjunctions of forms.

The building must be in harmony with the environment. The location of the building, size of the rooms, ornaments, colour and the time of construction are essential factors in Chinese geomancy. The ideal position for the sighting of an inland Chinese temple is on ‘the pulse of the dragon’, the favourable part of a hill, or the qi area. The geomancer determines the favourable location with his or her special compass, the luopan. Each direction has excellent or evil implications. The Northeast and Northwest are, for example, considered to be the doors of the devil.

The Bendigo Joss House is orientated with the main altar pointing to the north, which is in line with Chinese geomantic principles. The question to be asked is whether the geomantic principles described in Feng Shui literature are valid in the Southern Hemisphere.

The Joss House is set apart as a sacred space mainly by its colour, the ornaments on the roof and the signs on the front of the building. Geomancy does not set the temple apart from profane buildings. Feng Shui principles are widely used in profane buildings, city planning and burial sites. The temple is integrated with profane space, making all profane space sacred.

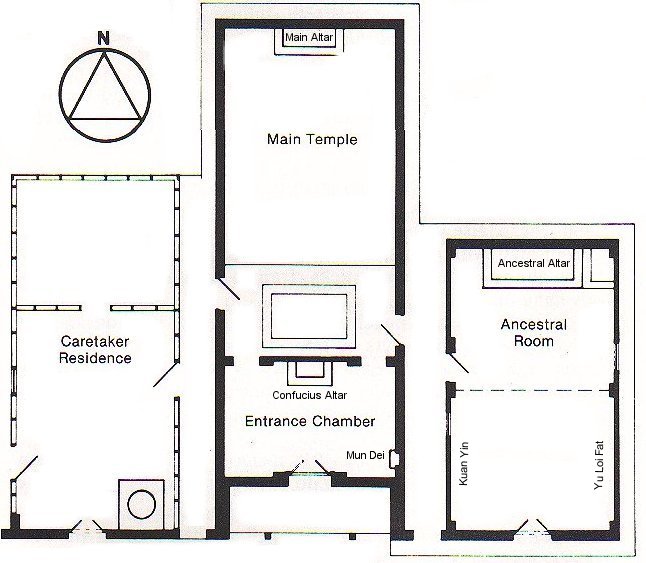

The Joss House consists of three small rooms: the Main Temple in the centre, flanked by the Ancestral Room on the east and the Caretaker Residence on the west. The layout of the building is almost perfectly symmetrical. Though very small, the temple contains many of the parts associated with similar though larger structures.

Situated above the central entrance is a large sign reading: ‘Big Gold Mountain Temple’, the original name for the Bendigo Joss House. Two vertical signs with Chinese proverbs flank the entrance: ‘The Hero brings prosperity to develop this land’ and ‘The generosity of the land gives great vision’. The primary access to the Joss House is not in use any more. Worshippers and tourists enter the temple through the Caretaker Residence. The residence houses religious artefacts, but these do not have a function in religious activity in the temple and will therefore not be further considered.

The central feature of the front Entrance Chamber is an altar with a figure of Confucius, flanked by two wooden panels with poems in Chinese script. To the right of the entrance is a little niche, containing a statue of the Door Guardian, Mun Dei. The guardian is an important symbol of the boundary, demarcating the sacred space. The walls of the Entrance Chamber contain stone rubbings and a framed quotation from Confucius: ‘You must do right in this world’. The Entrance Chamber is separated from the other sacred areas in the temple; it functions as a threshold for the worshippers that used to enter the temple through the main entrance.

The main altar of the Joss House is on the north wall of the Main Temple. The altar is dedicated to the Taoist deity Kwan Gung, a Chinese general who lived from 221-266 AD and was noted for his uprightness in addition to his military powers. Displayed in the left corner is an effigy of Day Fong San, the god of filial piety and wealth. He symbolises love and respect for parents. The altar also contains replicas of the Bodhi tree, under which Buddha meditated, which represents the centre of the world. It further holds many objects that are used by the worshippers in their religious activities, which will be discussed below.

The Ancestral Room is dedicated to the memory of their Ancestors. The altar consists of racks with three commemorative tablets to the deceased. Originally there were hundreds of memorials, but vandals destroyed most of them. On the left and right of the altar are wooden panels with Chinese proverbs. On the left: ‘If you do good to others, they will do good to you’ and to the right: ‘Don’t bear false witness’. The Ancestral room further contains two Buddhist altars. The West altar has a statue of Kuan Yin, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. The east wall contains an altar with a statue of the Buddhist Yu Loi Fat, the protector of the very poor. The framed pictures above the East altar depict the First Lord of Heaven, the Queen of Heaven and several other Taoist deities.

The Chinese are very pragmatic about religion, and their dealings with the transcendent are therefore not confined to one religion. The basic rule is that the more deities one prays or pays homage to, the more fortunate one will be. This practice is called Syncretism. Syncretism embraces ancient ancestor worship and the three fundamental religions of China: Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. The syncretic nature of the Joss House becomes apparent in the objects on display: the figure of Confucius in the Entrance Chamber, the Taoist deity Kwan Gung in the Main Temple, the worship of ancestors and the statue of the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy in the Ancestral Room, demonstrating the Chinese world view.

Devotees communicate with the deities through prayers and ritual. When a devotee is unsure about something in life, he or she will seek advice from the deities through wen bei, kidney-shaped divining blocks used to communicate with the gods. Another method of divination is wen qian. Qian are bamboo slivers, each marked with a reference number, in a bamboo container. The devotee shakes the container till one chip falls out. The number on the qian refers to a printed message from the deity, which is usually interpreted by the temple soothsayer.

The Bendigo Joss House does not have a soothsayer, but the Main Temple contains several books on the interpretation of wen qian for reference of the worshippers. The Joss House derives its sacredness through hierophany; the sacred is manifested to the believer through the iconography of the objects in the Joss House.

The many images, statues and quotations in the temple are a manifestation of the transcendental world of the deities in the immanent world of the believers. They are mediators of the religious experience sought for by the worshippers visiting the Joss House. The Joss House is a sacred space because of the presence of these images, statues and quotations. The use of geomancy in the architectural layout and orientation of the building also enhances the sacred character of the building.

Chinese temples usually serve as multi-purpose cultural and community centre, strengthening clan associations. The Joss House would have played an essential role in the social life of the Chinese miners in Bendigo, but the role of the temple in Chinese communities has changed in the last century. The Bendigo Joss House is still used for worship by the Chinese community and serves as a museum but has lost its social function. Its primary function is to provide a link to a heritage for Chinese in Australia.

The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart

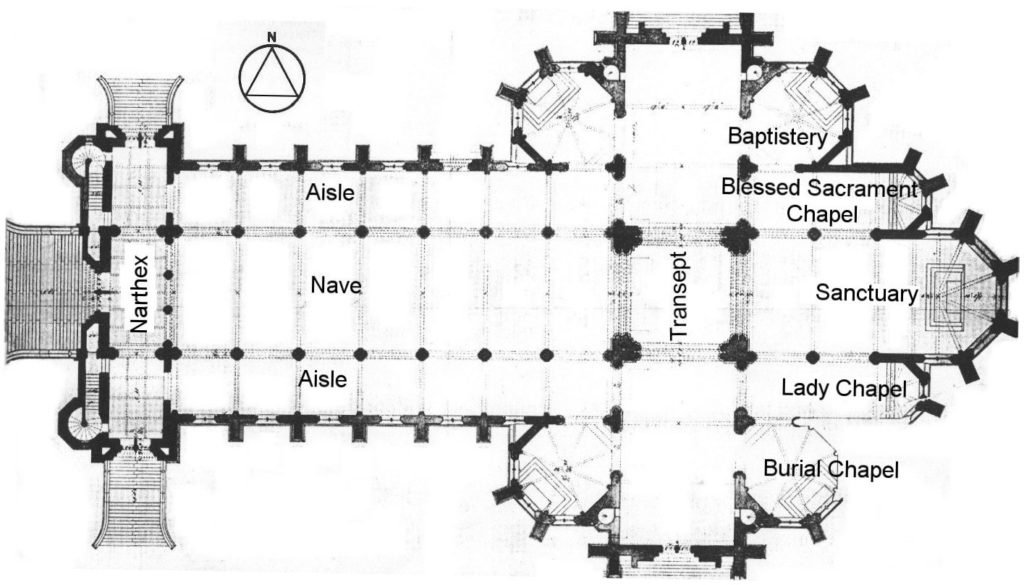

The Bendigo Cathedral is constructed in the English Neo-Gothic style of the nineteenth century, inspired by the medieval churches in Europe. Construction of the Cathedral’s nave and narthex began in 1896 and was completed five years later in 1901. Work on the building ceased in 1908 because of a shortfall in funding.

Construction recommenced in 1954, and the Cathedral was finally completed and consecrated 82 years later, in 1977. The Cathedral derives its name from the seat or throne, the cathedra of the Bishop, located in the sanctuary. The Sacred Heart Cathedral is the church where the Bishop of the Diocese of Sandhurst, Bishop Joseph Greg, celebrates various liturgical functions, especially the Eucharist.

The Cathedral is constructed of limestone on granite foundations, symbolising the eternal nature of the faith in the Christian god. The highest spire of the Cathedral measures 86 meters, and the total floor area is more than two thousand square metres. The architecture of the Cathedral blends medieval tradition with modern century construction techniques. Medieval people considered themselves an imperfect reflection of the divine light of God, and Gothic architecture was the ideal expression of this view.

The Cathedral has no inner walls separating the different areas, the central axis of the building is orientated east to west, with the main altar pointing east. Christian churches are traditionally orientated with the main sacred area towards the rising sun. The practice of praying, while turned towards the rising sun, is older than Christianity. The east to west orientation is also interpreted as the direction of the resurrection of Christ.

The ground plan of the central area of the Cathedral is cross-shaped, the cross is the most important sacred symbol of the Catholic religion. The shape of the Cathedral can also be interpreted as the body of Christ and the human form more generally. In the symbolism of the Byzantine church, for example, the nave represented the human body, the channel the soul, and the altar the spirit. Gothic churches can also be interpreted as a representation of the heavenly Jerusalem as described in the book of Revelations. The church as a community is understood as the city of God on earth, and the city of God is understood as a reflection of the heavenly Jerusalem. The heavenly Jerusalem is considered the axis mundi, the centre of the world. The Cathedral is an image of heaven as well as the human body; it reveals parallelism between the Microcosm and Macrocosm.

The Cathedral can be entered through five doors on three sides of the building. At each entrance, there is a little font filled with sacred water that the people who enter the Cathedral use for a short ritual before entering the Cathedral. The threshold of the sacred space is thus ritually demarcated from the outside world. The aisles contain fourteen paintings of the ‘Stations of the Cross’.

The paintings depict Jesus’ life from being condemned to his burial. The stained glass window occupying the most Western Wall shows Christ in the centre. On the left, his mother, the Virgin Mary and on the right is St Joseph, his foster father. On the left outside, we find images of St Augustine and St Patrick. The nave of the Cathedral is reserved for seating for the believers when attending mass. The central sacred area of the church is located at the eastern wing. The sanctuary in the middle is the most important sacred area. Standing in front of the sanctuary, five separate sacred spaces can be identified.

In the baptistery, the Sacrament of baptism is performed. Baptism is the main rite of passage of the Catholic Church, usually performed just after birth. It is only through baptism that a person can become a member of the church. In Medieval times special chapels to perform baptisms were built separately from the church to avoid that persons that were not baptised would enter the sacred space of the church.

To the right of the baptistery is the ‘Blessed Sacrament Chapel’. The chapel contains the Sanctuary Lamp, which burns continually to signify the presence of Christ, the light of the world. The sanctuary is the most important sacred area of the Cathedral. It contains the main altar, the ritual centre of the Cathedral. The front of the altar has a Latin inscription reading: Unigentius filius est in sinu patris (The only begotten son is in the lap of the father). Behind the altar, facing the people, is the cathedra or Bishop’s chair. It is there that the Bishop presides over the whole Diocese in his capacity of the chief pastor and is the link between heaven and earth.

Sanctuary of the Cathedral To the right of the sanctuary is the Burial Chapel. Beneath this chapel is the crypt in which the Bishops of Sandhurst are buried. The chapel contains a statue of Christ after he was taken down from the cross, signifying the function of the crypt below. Also here we find a Latin inscription: “/Requiem aeternam dona eis domine/” (The Lord gives them eternal rest). The function of the Cathedral is described in a pamphlet for visitors: “This Cathedral is built as a place where the People of God can gather, to hear the word of God, and to respond to God’s love with prayer and praise, sorrow and thanks, sacrifice and worship”. The purpose of any catholic church is to pray, the hearing of mass and the reception of the Sacraments. The ‘Sacraments’ are the most important religious experiences in Catholicism. Only initiated persons — the priest — can only perform the Sacraments. The church can therefore not be separated by its designated ritual experts: the priests and the Bishop.

Conclusion

In the classification of sacred space by Moore and Habel, the Cathedral and the Joss House are both considered temples. Moore and Habel define temples as Sacred buildings of traditional construction, which primarily places of communal worship. They are places ritually demarcated for contact with the divine and derive their sacred character from this ritual demarcation.

The Cathedral and the Joss House indeed have a lot of aspects in common. Both buildings serve or used to serve a social purpose. The Joss House has lost the social function, but the Cathedral is very much a place where the local Catholics gather and share their faith and culture. Both buildings are used for communication with the transcendent and the iconography of the building, and the objects are used as mediators for religious experience.

The Cathedral officially derives its sacredness from Consecration. Consecration, in general, is an act by which a thing is separated from a common and profane to a sacred use, or by which a person or thing is dedicated to the service and worship of God by prayers, rites, and ceremonies. The iconography of the objects in the Cathedral and the architecture of the Cathedral also play an essential part in the sacredness of the building.

The Cathedral is not only a building in which God is worshipped, but it is also the expression of an act of worship. The grandeur of the architecture itself is a mediator for a religious experience. In the Joss House, the architecture itself is of minor importance. The temple derives its sacredness mainly through the iconography of the artworks inside the temple.

The main difference between the two buildings is the symbol used to transform the space into sacred space. A Catholic entering the Joss House will not have a religious experience, and he or she will not pay homage or pray to the deities in the temple. A Chinese person may have a religious experience in the Cathedral, given the syncretic nature of their religious beliefs, but the cultural foundations of these experiences are very different.

The Catholic religious experience is numinous. The numinous experience is based on distance from the transcendent. The experience emphasises the gap between the human being as a creature overwhelmed by the otherness and power of the deity of the sacred. This distance is enhanced by the fact that the Sacraments can only be performed through a mediator and not received directly through private worship. The architecture of the Cathedral enhances the numinous feeling.

The religious experience sought for by believers in the Joss House is a mystical one. A mystical experience is, in many ways, the opposite of a numinous experience. This type of religious experience the oneness of the human and the divine or the self and the cosmos are experienced in such a way that all otherness disappears.

Although both sacred spaces share many characteristics, the fundamental difference in how the transcendent is experienced ensures that each building is only sacred to those people that share the cultural background of the religion.

References

- Sacred Heart Cathedral Bendigo, Pamphlet for visitors distributed in the Cathedral.

- Bourke, D.F., A history of the Catholic Church in Victoria, (Melbourne: Catholic Bishops of Victoria, 1988).

- Brereton, Joel P, ‘Sacred space’, in: Eliade, Mircea, editor, Encyclopedia of religion, Volume 12, (New York: Macmillan, 1987), pp. 526–535.

- Habel, Norman, O’Donoghue, Michael, and Maddox, Marion, Myth, ritual and the sacred, (Underdale: University of South Australia, 1993).

- Hasset, Maurice, ‘Orientation of churches', in: Catholic encyclopedia, (New Advent, 1911).

- Lip, Evelyn, Chinese temples and deities, (Singapore: Times Books International, 1986).

- Lucas, Herbert, ‘Ecclesiastical architecture', in: Catholic encyclopedia, (New Advent, 1909).

- Moore, B. and Habel, N., When religion goes to school, (Adelaide: SACAE, 1982).

- National Trust of Australia (Victoria), Bendigo and the Chinese Joss House, (Melbourne, 1972).

- Schulte, A.J., ‘Consecreation', in: Catholic encyclopedia, (New Advent, 1911).

- Stöver, ‘Kopie en navolging in het middeleeuwse bouwen (Copy and imitation in medieval architecture)', in: Kunst. Overlevering, verandering en vernieuwing. Essaydeel. (Art. Tradition, change and renewal. Essays), (Heerlen: Open Universiteit, 1998).

- Wheatley, Paul, The pivot of the four quarters: a preliminary enquiry into the origins and character of the ancient Chinese city, (Chicago: Aldine, 1971).

Share this content