Stoic Theory of Universals: The Case Against Nominalism

Peter Prevos |

1297 words | 7 minutes

Share this content

The problem of universals is the problem of correspondence of our intellectual concepts to things existing outside our mind. A universal is a property or relation that can be shared by several different particular things. Each yellow object participates, for example, in universal yellowness. This short essay discusses the stoic theory of universals and makes a case against nominalism.

The Stoics are nominalists and deny the existence of universals. Plato and Aristotle, on the other hand, are realists about universals because they assert that when we assign a property to a particular object—for example, “this lemon is yellow” and “this car is yellow” —that there exists something that is yellowness, shared by the lemon and the car.

A realist about universals thus claims that when a is F and b is F, there is some extra-mental and extra-linguistic thing—the universal F-ness—that is had by both a and b. Both Plato and Aristotle argued that if knowledge or understanding (epistêmê) is to be possible, then there must be universals. Both disagreed, however, on where and how the universals exist.

Plato’s theory of Forms

The distinction between Forms (eîdos or idéa) and particular sensible things is central to Plato’s metaphysics. Plato distinguishes in the Timaeus (28a) between that which “always is and has no becoming” and “that which is always becoming and never is”. This distinction has, according to Plato, epistemological consequences:

That which is apprehended by intelligence (nous) and reason (logos) is always in the same state. That which is conceived by opinion (doxa) with the help of sensation and without reason, is always in the process of becoming and perishing and never really is.

The text-book account of Plato’s philosophy is that his theory of Forms is a reaction to the philosophy of Heraclitus, who argued that sensible particulars are always in a state of flux.

Upon those that step into the same rivers different and different waters flow.

The argument for Forms from Heracliteanism, which might thus be credited to Plato, is:

- What we understand when we understand what justice, beauty, or generally F-ness are, doesn’t ever change.

- But the sensible F particulars that exhibit these features are always changing.

- So there must be a non-sensible universal—the Form of F-ness—that we understand when we achieve episteme.

The question that needs to be asked of Plato is how much change is acceptable for any particular thing, for example, a wombat, to remain a wombat? Any living wombat is always undergoing modification of some kind, even if it is only chemical changes involved in the digestion of its lunch. This notion seems to rule out that in understanding the definition of a wombat, one could be understanding any particular wombat. What we know when we understand the definition of a wombat is the existence of some species of ‘über-wombat’, existing outside the realm of physical reality, not the particular—ever-changing—wombat in nature.

Aristotle versus Plato

Both Plato and Aristotle are realists about universals. They, however, hold a different view about the relationship between the existence of universals and the particulars that participate in them.

Scholastic philosophers described Plato’s theory as universalia ante rem (before things), and they wrote that Aristotle had a theory of universalia in re (in things). This interpretation implies that Plato thought that universal properties could exist even if no particulars were participating in them—universals are transcendent to the world. Aristotle, on the other hand, thought that there could not be any universals unless there are also particulars participating in them—universals are immanent in the world.

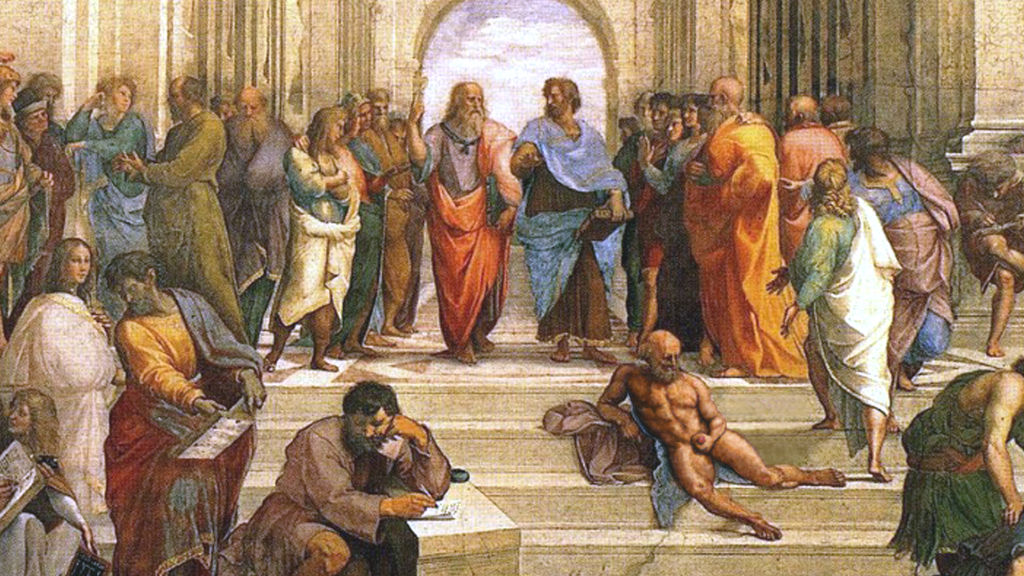

The difference in their theories is beautifully expressed in the School of Athens by Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520). In this fresco, Plato and Socrates are in the centre of the composition, with Plato pointing to the heavens and Aristotle pointing towards the earth.

Stoic theory of universals

The Stoic ‘not-someone’ argument is a continuation of Aristotle’s objection that if the Form of beauty could exist independently of beautiful particulars, it would itself have to be a particular. By this Aristotle seems to have meant that, if the Form of, for example, a chiliagon (a thousand sided figure, from: chilias—one thousand) could exist independently of any chiliagon-shaped things, then it would be a kind of super-sensible particular thing. The ‘not-someone’ argument is—according to the Neoplatonic philosopher Simplicius (527–565 AD)—invoked by the Stoics to disprove that universals are a ‘this something’, e.g. they neither exist nor subsist:

- Man is someone.

- If someone is in Athens, he is not in Megara.

- But man is in Athens.

- Therefore, man is not in Megara.

Sedley explains that: “If you make the mistake of hypostasing the universal man into a Platonic abstract-universal—if you regard him as a someone—you will be unable to resist the evidently fallacious syllogism”.1 The improper step is the substitution of man with someone. The argument can be fixed only by denying that universal man is ‘someone’ and subsequently that universals do not exist separately from particulars.

The Stoics distinguish two different ways of getting to know what is in the world. They are materialists in that they believe that only bodies exist. Meanings, time, place and void; however, don’t exist but subsist (huparchein). We could render the Stoic distinction between living and subsist by saying that “There is such a thing as a rainbow, and such a character as Mickey Mouse, but they don’t exist.” The Stoics say that the highest genus under which everything falls is not ‘existence’ or ‘being’ but ‘something’.

Any particular thing that can sensibly be talked about is a something, but not all somethings exist in the Stoic sense of the word. They introduced this terminology is to explain phenomena that we believe have some type of being (such as meanings, time, place and void), but fall short of the type of being which is familiar to us from our interactions with spatially located bodies. Universals are a not-something to the Stoics because they neither exist nor subsist. The Stoics say that universals (concepts) are “neither somethings nor qualified, but figments of the soul which are quasi-somethings and quasi-qualified”.

Against Nominalism

According to the nominalist, for a particular to have a property is for it to stand in a certain relation to a mental of linguistic thing, a concept or predicate. David Armstrong thinks that this makes the question of what properties particulars have a matter of how we classify things. He further argues that our categories are independent of the actual properties of objects.2

Whether for example, the throwing of a brick will break the window depends on the impulse of the brick (mass and velocity), the plasticity indices of the brick and the glass and the thickness of the glass. The brick would break the window, even if we had no concepts such as impulse and plasticity index.

Armstrong thus argues that basic properties exist independently and are not a matter of the classifications we make. The nominalist will, in response to Armstrong’s critique, simply deny that their view implies that we construct the world with our concepts in any way that negates the objectivity of relations of cause and effect. They hold that our classifications depend on and react to objective resemblances between things. Armstrong anticipates this objection by arguing that resemblance is so far from providing an alternative to universals that it presupposes them. Armstrong explains resemblance by appealing to shared universals. The resemblance nominalist takes resemblance as a brute matter of fact, but everyone must take something as a brute matter of fact, even Armstrong.3

Notes

Share this content