Computer Magic: Software Illusions and Deceptions

Peter Prevos |

1390 words | 7 minutes

Share this content

Arthur C. Clarke famously wrote that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. People from before the electronic age would see our computerised lives as filled with magic. Computer magic is not supernatural, but more like a magic show.

The first time I typed words on a keyboard and saw them appear on a screen was a magical experience. I gradually learnt to program my Atari 130XE, and a sense of magic was replaced by knowledge. My computer had a mere 64 kilobytes of memory, which is 250 thousand times less than the computer on which I am writing this article.

More skilled software developers and hackers wrote impressive demo programs to showcase the possibilities of these simple computers. Some of these demos exceeded what these machines were presumed to be capable of doing. Innovative programming techniques and optical illusions created a magical experience. These little programs were the magic shows of the 8-bit computing age because they seemed impossible to mere mortal computer users.

These computer demo programs don’t exist anymore because they are trivial to modern computers. But electronic sleight of hand is not only relevant to classic computers. All graphical computer interfaces and artificial intelligence are, in fact, a form of deception that helps users interface with the binary world. Artificial intelligence also has an aspect of benign deception.

Lastly, software can also assist magicians in performing their craft. Machine learning methods have been used to optimise magic tricks, and robots perform magic tricks. Magicians have always embraced new technology and regularly use advanced technology in their performance.

The Magic of Graphical Computer Interfaces

Software designers have looked at magicians to learn about human perception to design better computer interfaces. Bruce ‘Tog’ Tognazzini, an expert in human-computer interaction, writes that “Both software designers and magicians create virtual realities. We bring ours alive on computer displays; magicians bring their alive on the stage.”

Paul Haeckel was the first to identify the link between magic tricks and software interfaces. He recognised that, to the user, it is unimportant what the software actually does under the hood. Only the mental model matters to the user.

The computer screen shows us a world of buttons, pages, folders, and so on that do not really exist. When you drag a document into the trashcan on the desktop, you are not really deleting it. All you are doing is deleting a pointer to the file. It is still somewhere on the hard drive until it is overwritten. The mental model of deleting a document is thus very different to what really happens.

Just like a magic show, there are two parallel actions. The one that the user or spectator experiences, and the covert action of the magician or computer. The relationship between computing and magic is expressed in the portmanteau automagically. We don’t know how a computer does it, but it happens nevertheless.

The Magic Artificial Intelligence

Deception is an integral part of AI and robotics, and in some ways, they form a science of illusion. For example, you might think that you are chatting with a person. Still, in actual fact, you are responding to a string of words generated by an algorithm. The computer has no idea what it means, and we are deceived into believing we converse with a person.

Software developers don’t purposely use the same techniques as magicians, but perhaps they should embrace them. Swiss magician Marco Tempest suggested that:

“if Siri had been designed by a magician, she probably wouldn’t fail. It wouldn’t be either she knows or doesn’t know; there would always be another question. … We would use cold-reading skills.”

Artificial intelligence can also help magicians to optimise magic tricks. Any design process is a compromise between optimising the outcome within defined constraints. Artificial Intelligence can assist humans with optimising design problems because computers are much better at tracking the millions of possible permutations in a complex design.

Computer scientist Howard Williams has made great strides in developing algorithms that assist with designing magic tricks. One of his creations designed a magic trick using geometry and another a card trick.

Whether human creativity will ever be surpassed by augmented intelligence is an open question. No matter how smart an AI can become, they have no lived experience. Good magic tricks have relevance to the real world. They are born from our experience with the limitations of the physical world. This video from Jay Sankey provides some insight into the creative process he uses to develop new magic tricks.

Computerised Magic

The relationship between magic and science is bidirectional. Scientists study the craft of magic, and magicians use science to create the illusion of magic. Stage magicians have always embraced technology to further their craft. Software and robotics now play an increasing role in theatrical magic. Robot engineers can now build machines that perform magic tricks. Contemporary magicians, such as Marco Tempest, combine traditional magic with electronic tools.

Robot Magic

Magicians have used robots as magical props for some centuries. Von Kempelen’s automaton chess player is one of the first technological mysteries presented to audiences in Europe. This machine was able to play chess and beat many players. The machine was not presented as a technological achievement but as a magical secret. Although the machine contained an elaborate mechanism, its cabinet actually concealed a small chess player who controlled the machine.

French magician Robert Houdin started his professional life as a clockmaker. As a magician, he used his skills to build elaborate mechanical tricks and robots, such as a dancer on a tightrope and doing the cups and balls magic trick.

Husband and wife research team Noel and Amanda Sharkey of the University of Sheffield published a paper exploring the long relationship between stage magic and robots. They related the success of these machines by the fact that they resemble living animals or humans.

Japanese engineer Ryoma Koretake and his colleagues built a robot that can perform a second deal. This is a secret card move whereby the magician deals with the second card instead of the top one. They meticulously analysed all muscle movements that a magician makes when executing the action and built a robot to perform the trick. However, this robot did not look like a human and was merely a fancy card dealing machine.

In September 2017, the annual Humanoid Robot Application Challenge was dedicated to a humanoid robot magic show. Robot magic shows are now a common challenge in robotics competitions. Performance magic tricks have interesting challenges for robotics engineers. In addition, they are an entertaining way to advance the craft and science of robotics.

While these devices are undoubtedly entertaining, robot magic is still in its infancy, even with our advanced technology. While they might be able to achieve the technical finesse required to perform a trick, presenting one entertainingly is still outside the realm of technological possibility.

Virtual Magic Shows

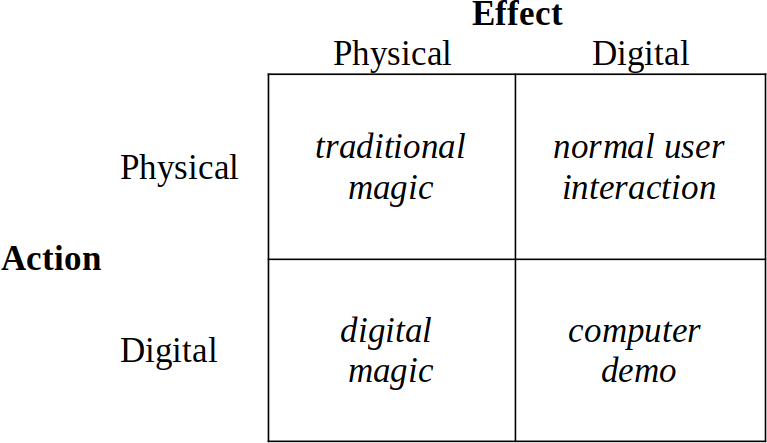

Spanish computer scientists Anna Carreras and Carles Sora experimented with combing traditional magic and digital technology in a special show. In a magical context, both physical and digital reality can interact with each other. In conventional magic, both the action and the effect take place in physical reality. So, for example, a magician can materialise physical objects from a screen (digital action with a physical effect). The diagram below shows the various options of interactions between the digital and physical world, illustrating how computer interfaces and magic are closely related.

Carreras and Sora found that traditional magic and tricks where a digital action affects the physical world received the best feedback from spectators. Of course, any effect in the digital world is merely a feat of technology and does not surprise spectators, but that does not mean that these effects have no theatrical value.

Swiss magician Marco Tempest is best known for his work with modern technology and for stretching the boundaries of what we expect from a magic show.

Computer Magic Bibliography

This bibliography contains journal articles, conference papers and books that discuss software from the perspective of theatrical magic. For a complete overview of professional and academic publications on magic, refer to the theatrical magic bibliography.

ERROR

Share this content