Aboriginal Art Symbols in Central Australian Dot Paintings

Peter Prevos |

2026 words | 10 minutes

Share this content

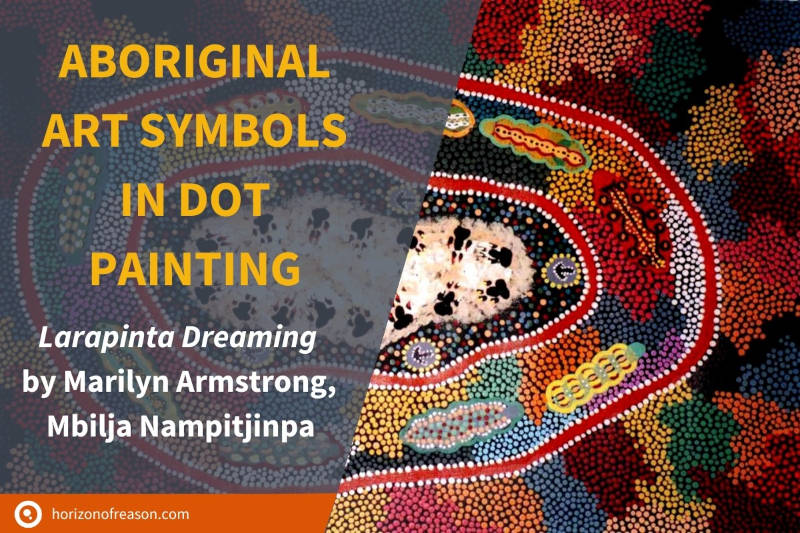

The ancestors of today's Aboriginal people populated the Australian continent about tens of thousands of years ago. Their culture is unique because, until the eighteenth century, they had limited contact with people outside Australia. One of the most striking manifestations of contemporary Aboriginal culture are the iconic dot paintings of the desert people. Dot paintings include many Aboriginal art symbols that convey meaning to the work. This article discusses the hidden meaning of Aboriginal art by analysing Larapinta Dreaming by Marylin Armstrong.

Before colonial times, Aboriginal culture was fully embedded in its natural environment. Aboriginal material culture revolved around practical and ritual objects. Craftsmen and women adorned spears, baskets, shields, and ritual and ceremonial poles with culturally meaningful patterns. Aboriginals expressed their art with natural materials such as rocks, sand, wood, bark, beeswax, reeds and occasionally bodily fluids.

The people of the Australian deserts traditionally expressed their art with sand drawings, painting their bodies, and the more enduring rock paintings and engravings.1

The Dreamtime

The Dreamtime is the defining aspect of traditional Aboriginal culture. This primordial period is the source of all social, legal, practical, and metaphysical knowledge. This time is retold through rituals and mythology. These rituals and stories contain all traditional knowledge handed down for generations. Sons learn these stories from their fathers and daughters from their mothers. Each Dreaming is owned by an individual or by a clan group. Most accounts of the Dreamtime are strictly confidential and known only to the initiates of the relevant Dreaming.

The stories of the Dreamtime feature mythical creatures that once travelled the land and created its current features. The stories of the On the surface, Dreamtime seem like a silly bedtime story for children. However, these myths contain a wealth of practical and cultural knowledge. A legend about an ancestral creature having a drink in a particular location indicates that this is a place to find water. Stories about relationships between Dreamtime ancestors might contain a lesson about human relationships. The Dreamtime was an essential storehouse of knowledge for a culture without writing.

The Dreamtime as a Knowledge Store

The owner of the Dreaming maintains the landscape associated with these stories. They are not owners of the land in the Western legal sense but custodians on behalf of the Dreamtime ancestors. They manage the land using traditional methods, such as fire-stick farming. The idea that Aboriginals were passive nomads is wrong because they took care of the land to ensure that food and water would be available. The Dreamtime stories gave Aboriginal people traditional knowledge about managing their land and society.2

These stories have a multi-layered logic. The seemingly simple stories at the surface hide profound practical and cultural knowledge. The logic of the stories or songs is a mnemonic device to help people remember large amounts of text.3 One of the methods to transfer this knowledge was through works of art. Traditional works of Aboriginal art are imbued with meaning. Aboriginal art symbols are used as a proto-language to communicate the Dreamings.

Aboriginal Art Symbols

The characteristic patterns of central desert Aboriginal art, such as the iconic dots and concentric circles, are a symbolic language that illustrates stories of the Dreamtime. Dot paintings are not the traditional domain of all Aboriginal peoples. The art of Arnhem Land, for example, is more figurative, with semi-realistic people and animals. Each Aboriginal nation or tribe developed its own distinct visual language.

The experience of Aboriginal art is different from the Western understanding. The most significant difference is that traditional art is entirely practical. The art used to be exclusively manufactured to share or enact the stories of the Dreamtime. Traditional art is, thus, a form of communication and a medium for transferring knowledge.

Body painting in rituals depicts events from the Dreamtime. Sand Mosaics are not just viewed but experienced by ritually singing and dancing through them, destroying the works in the process. Contemporary painters in central Australia derive their works from traditional sound drawings and body paintings.

Most Aboriginal artists produce their paintings horizontally on the ground by sitting around the canvas. This method is in contrast with Western art traditions, which are created vertically on an easel. Jackson Pollock is a famous example of an American painter who also places his canvases on the ground to paint. Museums display the works of Aboriginal artists almost always vertically, following the conventions of Western art. One exception is the Art Gallery of South Australia, which exhibits a monumental work of Clifford Possum horizontally.

Contemporary Dot Painting

Aboriginal art as we currently know it is relatively new and only became appreciated by a broader audience in the nineteen seventies. Geoffrey Bardon, who taught at Papunya Tula, brought this art to the attention of the Western world. Papunya Tula is one of many settlements for Aboriginal people, established by the Australian government in the middle of the last century. Officials forcefully removed people from their traditional land and taken to these settlements. This displacement caused immense stress because the government separated indigenous people from their traditional way of life.

After Bardon observed the importance of drawings in their culture, he provided the Papunya Tula men with materials to express their traditional art. As a result, the men painted a mural on a blank wall, which started the now world-renowned Central and Western desert art.

Modern materials like acrylic paint have opened a new world for Aboriginal artists. Traditional designs influence modern works but have lost their ritual purpose. This distinction also becomes evident in exhibition spaces. Art galleries display contemporary works, and anthropological museums exhibit objects such as baskets and boomerangs. However, the inspiration for both is the same: the stories of the Dreamtime.

The designs of Aboriginal art from the Australian desert are almost entirely abstract, and each painting has several layers of meaning. The meaning of Aboriginal art is therefore not apparent from simply analysing the patterns on the canvas. The true meaning of the work lies outside of the picture itself. The deeper meaning of Aboriginal art subsequently transcends the painting as a physical object. The meaning of all art, including the indigenous kind, exists on four different levels.

First level of meaning

The first level of meaning relates to the physical appearance of the work of art, including its materials, composition, colours, and so on.

On the first level, the famous dots in the foreground and background dominate paintings of the Australian desert tradition. The paintings generally do not include figurative elements but a culturally specific symbolic language of concentric circles, animal tracks and other shapes.

The paintings from the early modern period are almost entirely abstract. They are close to the traditional sand drawings from which they originate. Nature limits the traditional colour range to what is available in the environment. However, contemporary art in central Australia is freed from these limitations and uses more colours and symbolic elements.4

Second level of meaning

The second level of meaning relates to the physical reality of the work of art. The dot paintings depict the natural landscape that is connected with stories from the Dreamtime. The Dreamtime ancestors' activities shaped the land, resulting in the current geological structures.

Traditional sand paintings contained practical and cultural knowledge about the landscape and the tribe. On a practical level, these works of art communicated the places where water and food could be found. The cultural level contains knowledge about kinship and other social aspects of life.

As drawing in the sand has limitations, a rich symbolic language expresses the stories of the Dreamtime.5 This proto-language transferred practical and cultural knowledge between generations for thousands of years.

Third level of meaning

At the third level, the designs represent the ceremonies that re-enact the Dreamtime ancestors' epic journeys. Members of the clan perform these ceremonies as part of a cultural calendar throughout the year.

At this level, the multi-dimensional paintings express a series of events in time in one image. Aboriginal art can express a series of events besides a figurative image that usually shows a moment in time.

Fourth level of meaning

On the fourth and most profound level, the pictures contain spiritual knowledge known only to the Dreaming insiders. Only very little is, therefore, publicly known about this most profound level of interpretation since this knowledge is secret.

In traditional Aboriginal culture, the sacred and the secret almost fully overlap. This sense of secrecy can create tension with the unlimited curiosity characteristic of Western culture. Not only is it forbidden to share knowledge with outsiders, but even within the tribes, there are strict rules on the distribution of knowledge.

The emphasis on secrecy in Aboriginal culture can thus cause cultural tensions in the contemporary world. The website of the Art Gallery of South Australia used to warn about the esoteric content of the displayed works:

… this site may include images of a culturally sensitive nature. All efforts have been made to ensure that restricted works are not included.

The exhibition of works that depict secret stories has been problematic in the past. The drive of art enthusiasts to know the hidden meaning of paintings has caused artists to develop more complex and busy designs to obfuscate the deeper meaning of the paintings. Aboriginal Artist Tim Leura considers the patterns he paints on canvas to be mere toys. The serious work is painted on the bodies of people or the ground when undertaking a ceremony.

Larapinta Dreaming

I purchased Larapinta Dreaming in 2003 from one of the many galleries dotted around Alice Springs. Aboriginal art is popular among tourists, and a vital source of income for many Aborigines.

Larapinta Dreaming is painted in acrylic on canvas (63 x 41 cm) by Marilyn Armstrong from Hermansburg near Alice Springs. Marilyn was born in the Jay Creek community in the red heart of Australia. As a child, she came into contact with famous Aboriginal painters such as Albert Namatjira and Clifford Possum. In 1986, she started painting Dreamtime stories herself.

First and second level

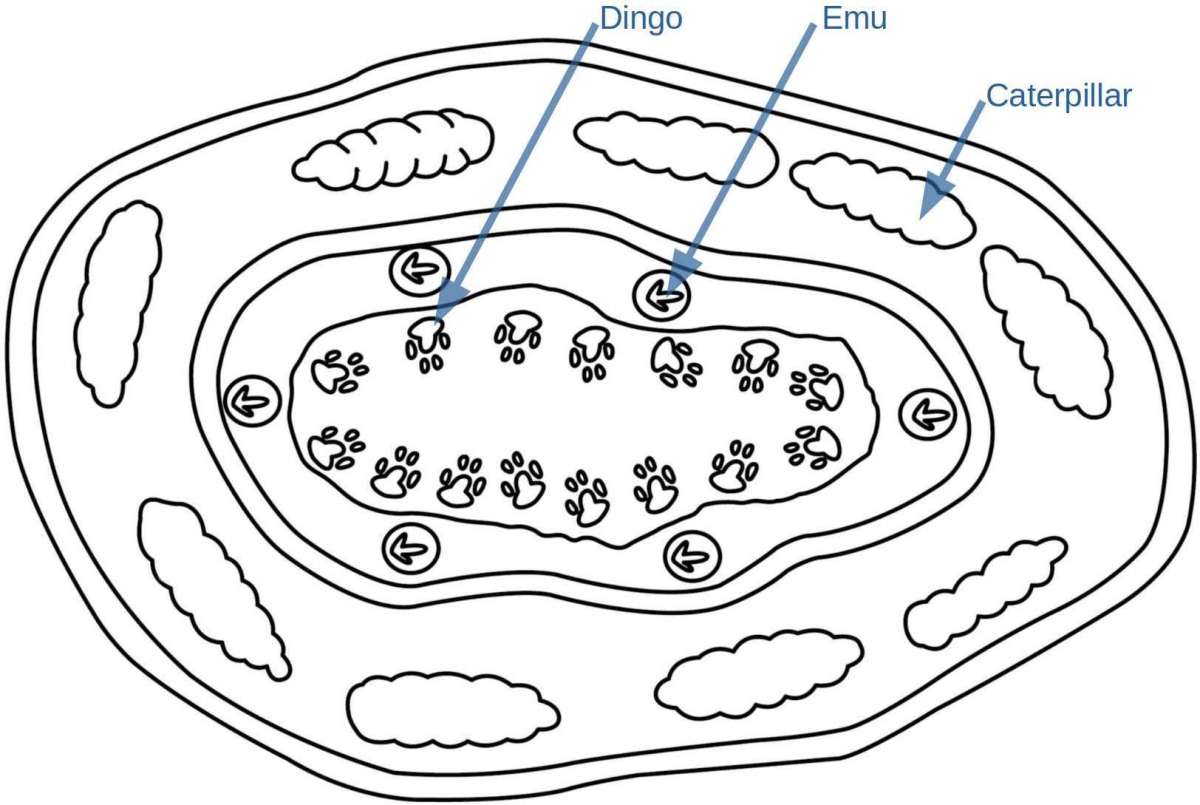

The most striking element of Larapinta Dreaming is the oval ring of caterpillars, the 'larapinta', encircling a collection of emu and dingo tracks. The background of the painting is entirely made of dots in varying colours, except for the central part of the composition. The colour palette of this work contains many bright colours, a recent development in contemporary Aboriginal art. The back of the painting reveals the second level of meaning:

This area got many sacred sites, and there is one where the dogs vomit. Other side is where the women had been meetings, dances and also the caterpillar dreamings where the Aranda people camp is.

Marilyn Armstrong, Mbilja Nampitjinpa.

On the second level of meaning, this painting refers to the MacDonnell Ranges, the geological formations around Alice Springs that look like caterpillars, as shown in the photograph above. At the third level, it perhaps references an unnamed women's ceremonial place in the MacDonnell Ranges.

Deeper levels

Since I have not been initiated into the deeper meaning of the Larapinta Dreaming, I cannot comment on its ceremonial and metaphysical significance, which constitute the third and fourth levels of meaning.

I could speculate that since a woman painted this canvas, the vomiting might be related to the morning sickness of pregnant women, and this painting refers to a place where pregnant women gather and share knowledge with the elders. However, this is pure speculation on my part.

Footnotes

Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H. Berndt, The world of the first Australians. Australian traditional life: Past and present (Fifth edition, Canberra 1996).

Bardon, Geoffrey, Papunya Tula. Art of the Western Desert (Marlston 1999), pp. 2-3.

Lynne Kelly (2016). The Memory Code. Allen & Unwin.

Stokes, Deidre, Desert Dreamings (Port Melbourne 1993).

James Cowan. Aborigine dreaming (London 1992).

Share this content