Climbing Uluru: Culture Clash in the Australian Desert

Peter Prevos |

2015 words | 10 minutes

Share this content

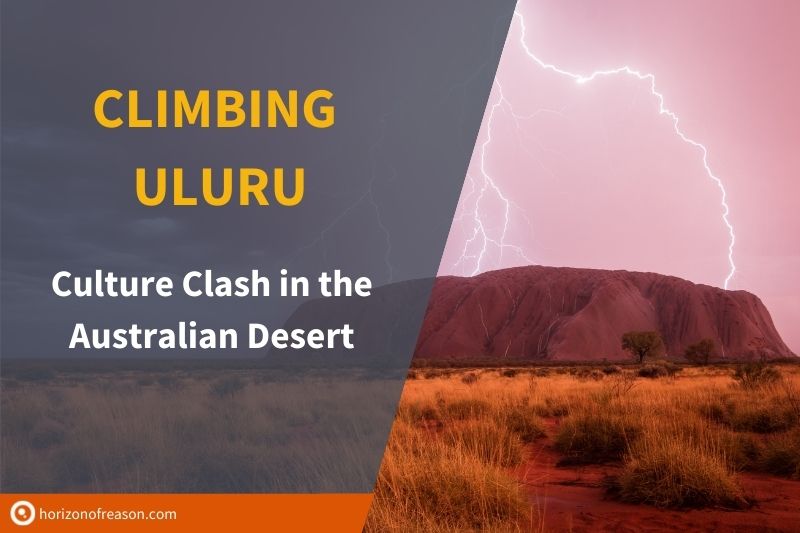

Uluru is a place of deep spiritual and cultural significance to the local aboriginal people, the Anangu. It is also an important tourist destination which has become the most recognisable symbol of the Australian outback. People from around the world flock to Uluru, or Ayers Rock to some English-speakers, and marvel at its mysterious beauty.

Many tourists travel with a simple maxim: “leave only footprints, take only pictures”, which is a maxim of ethical tourism. For the Anangu, however, this principle conflicts with their idea of respect for a place of spiritual significance, such as Uluru. Leaving footprints by climbing Uluru and taking photos of sacred spaces around Uluru is not acceptable in Anangu culture.

This article discusses some of the reasons for these cultural tensions between the traditional owners and visitors. This article delves into the cultural differences between the local Anangu and the tourists as a source of these issues.

The cultural difference between traditional owners and tourist is immediately apparent by the fact that this place has two names. The Anangu name for the rock is Uluru, while in English this place is known as Ayers Rock. Each of these names gives a different perspective on this location.

The Anangu Perspective: Uluru

Uluru is more than a geological feature to the Anangu. The rock is the omphalus of local aboriginal culture. Geologists call it a monolith, but Uluru is not one single spiritual object. The formation and creation of the specific characteristics of Uluru are the outcomes of several stories and myths which are not necessarily connected.

People with scientific education often discard mythology as patently incorrect stories. A myth is, however, more than a literal telling of past events. Mythology is a repository of knowledge about the land and the people and Uluru, and Kata Tjuta are significant features in local mythology.

The stories about Uluru are based on the Tjukurpa of the Anangu people. In western cultures, the Tjukurpa is frequently described as dreaming or Dreamtime. This translation is inaccurate because the Tjukurpa does not refer to ideas obtained in a dream. Tjukurpa is the sum-total of knowledge for the traditional local owners. This knowledge exists at several levels; from basic knowledge about nature to knowledge about social norms and more secret spiritual knowledge.

The ancestral beings travelled across over the country, creating all living things and landmarks we see in the desert landscape today. The mythologies connected to these beings are not merely bedtime stories for children, but they reveal knowledge about plants and animals and where to find water and food. These stories also teach people about social customs and everything else they need to know to thrive as human beings.

The local people can read the geological features of Uluru like a book. Many of the crevasses and scars on the rock remind them of the Tjukurpa stories and the knowledge that is contained within them. In this way, the geology of Uluru is a natural encyclopedia, and its geological features are heuristic devices to remind initiated people of their collective knowledge.

The deepest levels of Tjukurpa are surrounded in secrecy; the details of all the stories cannot be told publicly. Most Australian Aboriginal words which may be translated as sacred imply some degree of secrecy. The sacred and the secret often go hand-in-hand in many cultures around the world. It is, therefore, neither possible nor permissible to fully understand the complexities of the Tjukurpa. Only a few public stories about Uluru are known to the uninitiated. These stories are displayed on signs around the rock.

Kata Tjuta, another nearby monolith Uluru, is an incredibly important area, managed only by initiated men. For this reason, there are no Tjukurpa stories which can be told to the casual visitor, and all we can do is marvel at their geology.

The Tourist Perspective: Ayers Rock

The tourists generally don’t know Uluru under its original name, but Ayers Rock, which is the name given by the colonialists. Europeans first mapped Uluru and Kata Tjuta in 1872 when constructing an overland telegraph line. Insensitive to the existing local culture, they called them Ayers Rock and The Olgas.

The purpose of any non-Anangu visiting Ayers Rock is recreation. In the early days of tourism, visitors stayed right next to the rock, thereby desacralising Anangu sacred space. After the land was handed back to the original owners in 1985, the Ayers Rock Resort was built at a safe distance from the rock, and the sacred sites were reinstated.

To the visitors, Ayers Rock is a geological wonder of the world. No creation myths are explaining the origins of the monolith, but scientific geological theories. More than half a billion years ago, a river ran through the Peterman ranges. The eroded sand formed large deposits. After millions of years of geological changes and movements in the earth’s crust, Uluru and Kata Tjuta emerged as they appear today.

The two big attractions for the visitors are the sunset at Ayers Rock and for some climbing to the top of the rock. Climbing Uluru is almost like an initiation ritual for Australians. The Anangu disallow visitors from climbing the rock. Before 2019, climbing was only discouraged, but most visitors ignored this advice. What visitors call the climb goes over the traditional route taken by ancestral Mala men on their arrival at Uluru. Because the path is of spiritual significance to the Anangu, they don’t climb the rock.

In addition to the climbing ban, some areas cannot be photographed. These sites are fenced, and warning signs indicate that it is forbidden to enter these sites or even photograph them, sanctioned with a $5,000 fine.

Not being able to either leave footprints or take photos goes against the maxim of ethical tourism. The best way to explain these differences is with reference to theories of scared space.

Uluru as a Sacred Space

The Anangu and the visitors experience Uluru quite differently. In the scientific view of these monoliths, the individual features of Uluru are the result of random processes that exist without any extrinsic meaning. This experience contrasts with the Tjukurpa view of the world where the landscape is imbued with meaning and knowledge through stories.

Uluru is a sacred space to the Anangu with, while to the visitors, the rock is a geological feature with scientific interest. There are fourteen individual sacred sites Around Uluru. Two of the sites are a part of the Tjukurpa celebrated by women and must not be entered by men or uninitiated women. For the Anangu, the sacred sites have a different quality than the other parts of Uluru.

Uluru is the hierophany of the Tjukurpa, a manifestation of the ancestral beings in the profane world. Ayers Rock is the result of a very long geological process. These two explanations of this place are at potential tension with each other.

The tension between the two experiences of Uluru becomes clear in the following passage taken from the pamphlet’ Welcome to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park’ distributed by the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre:

The tourist comes here with the camera taking pictures all over. What has he got? Another photo to take home, keep part of Uluru. He should get another lens to see straight inside. Wouldn’t see big rock then. He would see that Kuniya is living right inside there as from the beginning. He might throw his camera away then. (Tjamiwa).

Eminent scholar of religion, Mircea Eliade, described the differences between the sacred and profane experience of space. He states that for religious man, space is not homogeneous; there is a qualitative differentiation in space. In the profane experience, space is homogeneous and neutral; there are no qualitative differences. In Aboriginal culture, sacred space is an arrangement of the natural environment. In the cultures of the visitors, sacred spaces, such as temples and churches, are constructed.

The cultural tensions associated with Uluru derive from this fundamental difference in how people experience space whether you view Uluru as a geological feature or a hierophany of the lives of the ancestral beings.

Eliade further argues that we must not confuse the concept of homogeneous and neutral geometrical space with the experience of profane space since the profane experience is never found in a pure state. Although the visitors do not subscribe to the same religious beliefs as the Anangu, the experience of Uluru is not a profane one. The experience of profane space includes values that recall the non-homogeneity peculiar to the religious experience of space. Even without the background of Tjukurpa, Uluru—or if one prefers, Ayers Rock—is an inspirational natural monument.

The geological theory about Uluru is in many ways equally steeped in mystery as the Tjukurpa. The concept of hundreds of millions of years is beyond easy comprehension for any human. Anyone visiting Uluru cannot escape a feeling of awe about the place. The magical colours that Uluru displays in different lights, the vastness of the landscape and the enigmatic view of this gigantic monolith are unforgettable sights. For the visitors, space is homogeneous; there is no qualitative difference between one spot or the other. The fence acts the threshold to the sacred site, a warning to the uninitiated who do not know the Tjukurpa.

The maxims to leave only footprints and take only photos conflicts with the Anangu idea of respect for a place of spiritual significance, such as Uluru. Leaving footprints by climbing Uluru and taking photos of sacred spaces around Uluru is unacceptable in Anangu culture.

Anangu culture centres on the exclusivity of knowledge. This knowledge is only available to initiated members of the tribe. Because the geological features of Uluru contain knowledge about their culture, even looking at some parts of the rock is taboo for the uninitiated. For this reason, the Anangu do not want visitors to photograph certain parts of Uluru or to leave footprints on the rock, in contradiction with the maxim of ethical tourism.

This concept is hard to understand for visitors from Western and Asian cultures. For visitors, knowledge is not sacred or secret, but available to everybody (note the minor difference between these two words). Another difference is that visitors see nature as something they can enjoy, while for the local owners, nature expresses their culture. Many visitors don’t realise that Uluru is not merely a geological formation, but a sacred site and cultural experience.

The local ban on leaving footprints and taking photographs is hard to understand for some visitors. While the Anangu have every legal right to set the conditions to visit this place as it is their private property, the cultural reasons for these limitations are much more compelling than legal fact.

If the cultural reasons not to climb Uluru are not enough to convince anyone, perhaps the commemorative plaques at the base of the former climb will help. These plaques mention the names of some of the people who died climbing Uluru.

Uluru is not the only place in central Australia that cannot be photographed. The secretive Pine Gap facility near Alice Springs has similar limitations. The ban on leaving footprints and taking photographs for Pine Gap and Uluru are not that dissimilar. Both the base and Uluru are places of secret knowledge. The underlying principle for both sites is that knowledge is power. The knowledge of the Anangu gives them power over their land and their culture. The knowledge related to Pine Gap gives countries control over their land and culture.

References

Australian Nature Conservation Agency and the Mutitjulu Community Incorporated, An insight to Uluru, 1990.)

Ronald Berndt and Catharine Berndt, The world of the first Australians, (Canberra: Australian Studies Press, 1996).

Kerle, Anne J., Uluru, Kata Tjuta & Watarrrka: Ayers Rock the Olga’s and Kings Canyon, Northern Territories, (Sydney: UNSW Press, 1995).

Mircea Eliade, The sacred and the profane, (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1959).

Share this content