The Social Importance of Rites of Passage and Initiations

Peter Prevos |

1936 words | 10 minutes

Share this content

The word ritual has a negative connotation in our largely secularised society. Sigmund Freud described religious rituals as an “obsessional neurosis”.1 Since Freud, rituals are often described as habitual actions that are performed with a false belief that they will change the world. This article shows that initiation rituals, also known as Rites of Passage, are more than neurotic activities devoid of efficacy. Rites of Passage are full of meaning, also in a secularised world.

Rites of Passage are most commonly performed in a religious context, such as Christian baptisms or the more extreme land diving ritual in Vanuatu. Initiations don’t only occur in a religious context. Universities have hazing, and graduation rites of passage and many magic clubs have formal initiations. There is no significant difference between those rituals performed in a religious context and the ones we experience in our secular life.

The Meaning Rites of Passage

The anthropological understanding of a ritual is much broader than a repeated meaningless activity. A ritual is a traditional and ordered sequence of actions in which participants achieve a purpose through an interplay between the sacred and the mundane world.2 Participants perform religious rituals to achieve various objectives:

- Communication: Enable communication between the sacred and the profane, such as glossolalia, or speaking in tongues.

- Reconstitution: Rituals that accompany seasonal or cosmic cycles, such as Easter and Christmas, which are originally pagan celebrations to mark the changing seasons.

- Celebration or memorial: Remembering either good or bad past occurrences. These events can have taken place in the physical world or the mythological realm.

- Cleansing: Unite the secular and spiritual world closer together. These rituals enhance the quality of profane space.

- Promotion or protection: Funerals are a rite of protection because they ensure that the soul of the deceased is guided in their life after death.

- Initiation (Rites of Passage): A guided process of transition of a person from one state to another.

Rites of Passage

A rite of passage is a particular type of ritual, conducted to mark an important transition in somebody’s life. These rituals most commonly follow people from the cradle to the grave. An initiation transforms a person from their current state to a new one.

Rites of passage have multi-layered meanings. The purpose and intent of the ritual can be social or psychological as well as spiritual or religious. Certain rites of passage represent first and foremost transformations in the religious status or circumstances of the initiated. Catholic initiation rituals primarily have a spiritual meaning.3

“By Baptism we are born again, Confirmation makes us strong, perfect Christians and soldiers [. . . ] Matrimony, primarily affects man as a social being, and sanctifies him in the fulfilment of his duties towards the Church and society. Extreme Unction removes the last remnant of human frailty, and prepares the soul for eternal life”.

Initiation rituals are not limited to Catholics and form part of every society around the globe. Within our great cultural variety, we find many commonalities in the way these events are structured. French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep (1873–1957) is famous for his analysis of Rites of Passage. In his book Les Rites de Passage (1909), he shows that these rites include three phases:

- Separation

- Transition

- Reincorporation.

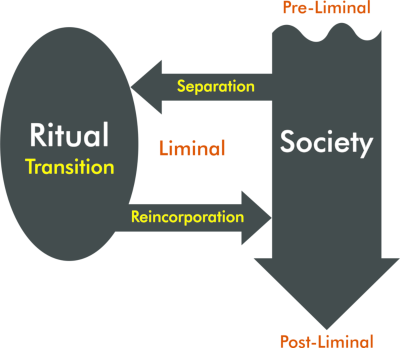

Each initiation ritual has three stages, the pre-liminal, liminal, and post-liminal stage. The Latin word limen is a threshold, and the liminal world forms the threshold between the old and the new. The diagram shows how an initiation ritual, temporarily removes a person from their society, transforms them and places them back into the community in a changed state.

Separation

The sponsor (the guide of the initiate) removes the initiate physically or symbolically from the world they currently form part of. This phase can involve removing clothing or wearing ceremonial garb. In some cultures, the separation phase can also include modifying or even removing body parts, such as tattoos or circumcision. After the separation phase, the initiate resides in the liminal world. The initiate is no longer part of the old world, but not yet accepted as a member of the new one.

Transition

After the initiate is disconnected from the old world, the transition phase starts. This is the phase where the initiates are instructed on the responsibilities of their new life stage. In this condition, they are often considered to be in danger themselves, or to others. To mitigate this negative influence, they are provided with a sponsor whose role it is to protect the candidates.

Reincorporation

In the final step of the tripartite, the initiate is confirmed in his or her new status; the initiate crosses the threshold so to speak. These rites may include spitting on the new member or investing the candidate with new a new name, clothes, rings, tattoos or other identifying marks. These marks of identity publicly announce that the individual belongs to the new group or status.

Profane Initiation Rituals

To non-religious people of contemporary society, initiation rituals seem a cultural practice from a distant past or performed by exotic tribes and secret societies. Initiation rituals do, however, also play an essential role in secular society.

Universities are the cornerstone of our secular society and centres of rational thinking. One of the distinguishing features of secularism is that many aspects of religion are replaced with science. Even though most universities are devoid of religion, rituals nevertheless play an essential role in the life of students and academics. Universities as centres of rationality are in some aspects also centres of irrational ritualistic activity.

We could argue that the years of going through university are in effect a very long initiation ritual. The student is removed from parental care and provided with knowledge and skills to become members of society after graduation. The actual studying can be referred to as the Rite of Transition. It is during this stage that the student consumes the knowledge presented by the ‘elders’. The final graduation ceremony is the Rite of Incorporation. The student is through this ritual, accepted as a member of the academic community. This long-term period is for many students punctuated by two specific rites of passage.

Hazing

Being a student is not only about learning but also about being a part of the student body. Hazing of new students is an informal rite of passage that marks a transition from a child to a student.

The act of hazing new students before they are accepted as members of a fraternity or sororities is at times controversial. The media focuses on violent excesses of this rite of passage. Still, it is an integral part of student life that marks a path to adulthood.

Most hazing rituals follow the three-part structure describe above. First, the student is separated and in a state of transition. Initiates endure adversity during the liminal phase, after which they are accepted as members of their chosen society. Hazing rituals are controversial because of their links to violence. Even though this might be unacceptable in contemporary society, it has formed a part of humanity for millennia.

These contemporary rituals have a lot in common with more traditional versions. In traditional Australian aboriginal societies, initiation rituals included violence through bodily mutilation, often using various bodily fluids, to represent ritual death. We have become squeamish about such aspects of humanity. Still, these types of rituals have been part of humanity for millennia.4 Student hazing is merely an expression of these millennia-old psychological mechanisms.

The Ritual of Graduation

Almost every university in the world performs a graduation ceremony to mark the end of several years of hard work. The pomp and circumstance of the academic dress and procession seem innocent reminders of ancient traditions to add gravitas to the moment of graduation. The ritualistic aspects of the ceremony such as the doffing of the hat to the Chancellor are, however, all part of an elaborate pagan ceremony.

One particular moment, the’ conferring of the degree’, can only be described as a moment of secular magical. This act is not magic in the sense that the ceremony has an ethereal atmosphere, but magic in the literal sense of the word. The conferring of the degree is in its very essence, a mystical moment.

In the ceremonies I participated in, graduands were asked to stand, and the Chancellor conferred the degree upon us. Even though she did not use any incantations or invoke any occult forces, the conferring of the degrees is a moment of magic. Only from that point forward that I call myself a Doctor of Philosophy. Even those who decided not to attend the ceremony did not escape the magical powers of the Chancellor, as also they had their degrees conferred upon them by the power invested in her.

It seems rather strange that a rational organisation such as a university uses archaic and irrational practices to finalise several years of intense rational work. Although the purpose of academic education is to hone logical thinking skills, the process is concluded this non-rational moment.

Although it might not be sensed by contemporary graduands as being just that, there is no significant difference between the conferring of the degree and the activities of a witch doctor or priest bestowing a blessing upon the believers.

Rites of Passage Meaning and the Horizon of Reason

Some scholars, like Robert Brain, stress the psychological importance of rites of passage. Brain asserts that Western societies do not have initiation at puberty to mark the path to adulthood. Without a ritualised path to adulthood, we have disturbed teenagers and infantile adults. At the age of eighteen, teenagers are magically converted into adults through statute law.

Brain is, however, wrong in assuming that Western culture does not have any rites of passage. Besides the religious rites of passage—such as practised in the Catholic Church—there are numerous examples rites of passage in Western secular culture. The rituals may be less ceremonial and without the intent of actually being an initiation, but the psychological drive is still apparent. The most noticeable difference between secular rituals and examples from other cultures is the intent of the activity.

Secular initiations are informal, and participation is voluntary. In postmodern western society, one can choose to marry or decide to be buried formally. In many other cultures, you are not a human being until he has undergone the rites of passage appropriate for his age and sex. For these people, there is no choice to participate in the ritual or not. Studying at a university is in a certain way a three or four-year initiation to eventually become a member of the academic community.

This article describes how the three-fold structure of Rites of Passage can still be found in contemporary society. Even though the spiritual aspects of ritualistic behaviours are no longer relevant in an atheist society, our psychology benefits from the structures that evolved over thousands of year.

Initiation rituals exist on the horizon of reason. There is no quantitative difference between the initiate and the initiated, but a qualitative improvement to their lives. Academic rituals are only a few of the examples of how these millennia-old psychological structures persevere even when their religious context no longer relevant.

Notes

Freud, Sigmund (1907). Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices.

Moore and N. Habel, On religion related to education, (Adelaide: SACAE, 1982), p. 204–209.

D.J. Kennedy, ‘The Sacraments', in Catholic Encyclopaedia, (New Advent, 2001).

Brain, R. (1979). Passage to Adulthood. In Rites Black and White (pp. 125–149). Ringwood: Penguin.

Share this content