Kinship analysis for a Dutch hamlet of Heugem in 1796

Peter Prevos |

2472 words | 12 minutes

Share this content

Humans form a web of relationships with each other. These relationships can be genetic through birth or social through friendships and other connections. One of the types of relationships that define societies is kinship, which is a system of relationships. Anthropologists analyse kinship to understand how societies function. Kinship analysis is a series of techniques to understand these relationships. This article explores the meaning of kinship for the of inhabitants of the 18th-century Dutch village of Heugem.

The main question is to what extent geography confined kinship within this community. The second question is how, in a deeply connected community, the people of Heugem observed marriage impediments.

The preliminary results of this research show a strong relationship between kin and geography in this village. The results suggest that kinship formed a social boundary within Ancien Régime communities in the southern Netherlands.

An earlier version of this paper appeared in the proceedings of the XXXth International Congress for Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Maastricht in 2012.

The township of Heugem

Heugem is currently a suburb of the city of Maastricht, in the south of the Netherlands. In the eighteenth century, it was an independent parish in the county of Gronsveld, which was a member of the imperial circle of Westphalia.

The town was economically dependent upon Maastricht. Heugem consisted mainly of market gardens that supplied fruit and vegetables to the city. Heugem lies in the fertile floodplains of the Maas, and many of the older inhabitants of the town would have suffered losses due to the great floods of the last half of the eighteenth century.

In 1794, Maastricht capitulated to the French imperial armies and not long after the French incorporated the region into their empire. The town became part of the canton of Eijsden, within the department of Meuse-Inférieure. The French occupier undertook a census on 21 April 1796. This census and the baptism, marriage and death records of the local and surrounding churches form the foundation of this research.

Kinship as a social boundary

Kinship is the language of social structure and as such fundamental to human relations. Although increased individualism has reduced the importance of kinship in contemporary societies, family relations structured past social life.

Kinship is a social construct; it is a value system concerned with the relatedness between people that determines who we consider relatives. The relationships are, in essence, free of biological influence. Anthropologists distinguish between the 'pater' as the social father and the progenitor as the biological father.

Kinship is the network created by genealogical connections and other social ties, modelled on the natural relations of genealogical parenthood. The nature of kinship depends on the cultural framework. Different cultures place varying emphasis on certain types of relationships, and not all biological relationships are of the same value. European cultures usually perceive relationships between siblings as having greater importance than relationships between cousins.

Kinship includes more than just the people who live together in a household. In the time before the great revolutions of the late eighteenth century, the connections between family members was strong. Kinship could stretch to relations distant in genealogy as well as geography. Distance or frequency of contact was not the main determinant for the strength of the tie.

Kinship analysis is a set of tools to investigate social structure and the various ties between people. Kinship analysis goes beyond standard genealogical research because the group being analysed is not a standard genealogy or pedigree, but a whole or part of a community.

The Catholic Church and Kinship

As an underlying social principle, kinship influences human behaviour and provides substance to interpersonal relationships. The Catholic Church studied kinship because it moderates reproductive behaviour. The prime objective was to avoid marriages between biological relatives.

A church decree from the 11th century explains that marriage rules were important because they prevented couples from having unhealthy offspring. If two related people wished to get married, the church required a dispensation for up to fourth-degree relationships.

Several justifications for obtaining a dispensation to marry a relative were acceptable: a small population resulting in a limited pool of potential partners, protecting family possessions and legitimisation of existing or foreseeable future extramarital relationships. The church also accepted girls that were too old to wait for a more suitable husband as a justification for dispensation.

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, recognised three types of kinship:

- Consanguinity (genetic)

- Affinity (legal)

- Ritual (spiritual)

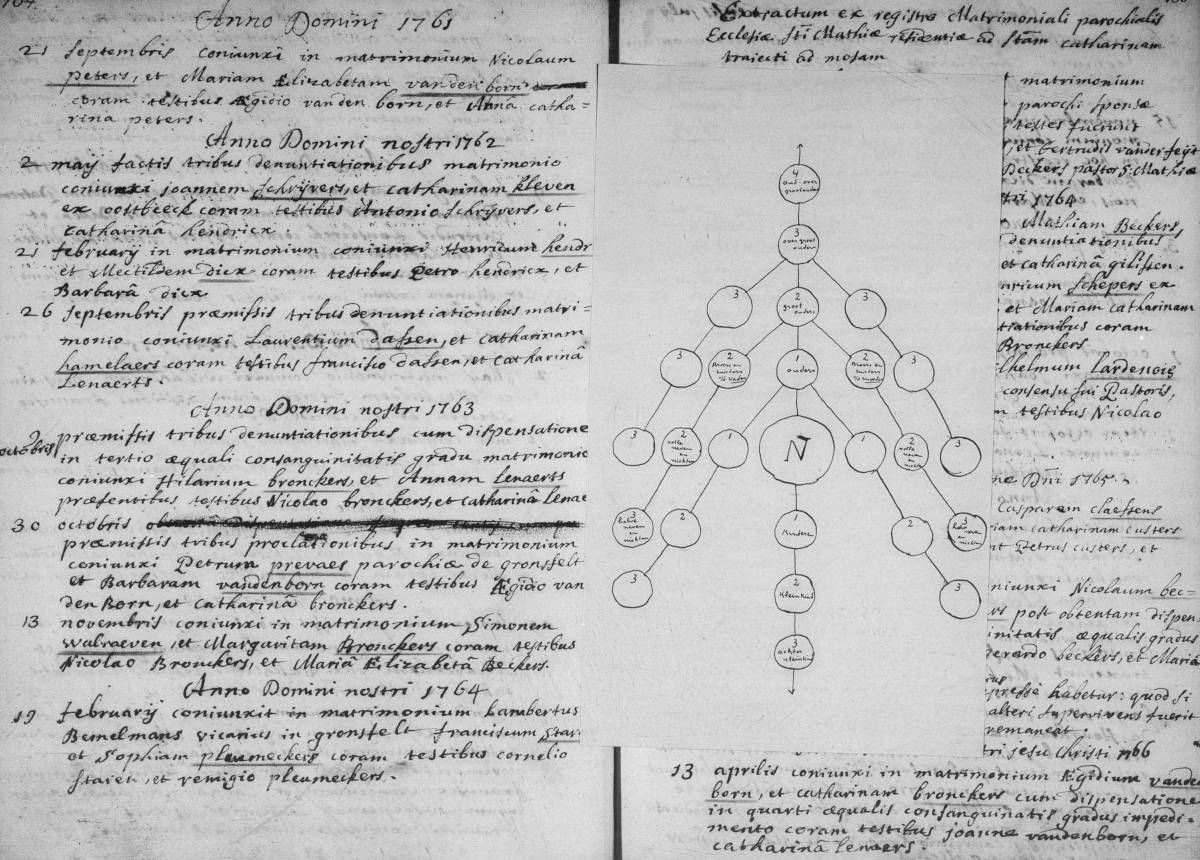

The baptism register of the town of Heugem contains a loose sheet on which the priest has jotted down a diagram to illustrate the degrees of consanguinity. He would have used this to help determine the degree of relatedness between marriage partners. This sheet illustrates the importance of consanguineous kinship and preventing intermarriage to the local priest.

Affinity is a relationship created through marriage (in-laws). For these relationships, marriage impediments only existed up to the second degree.

Ritual or spiritual kinship exists within the Catholic context through baptism and confirmation. Before Trent, ritual kinship was a means to establish networks of social alliance with often many godparents per child. Tridentine law ended this custom and set a limit of one godparent per gender. Baptism created a spiritual link between the priest, the child and the parents, and between the child and the godparents.

The church banned biological parents from being godparents as it would create an undesirable marriage because husband and wife would become each other's ritual kin. In the eighteenth century, parents preferred genetic relatives as godparents to prevent additional marriage impediments created by using non-related godparents.

Kinship Analysis

Kinship research is traditionally undertaken by anthropologists who scrutinise individual relationships through direct participant observation. To study kinship in detail requires access to systematic data encompassing the whole community under examination.

For historians, the task of reconstructing kinship is more complicated than it is for anthropologists. The records of the richness of the social reality of the past is incomplete. The administrators of the past created these for a specific context, usually other than reconstructing kinship networks. In some cases, we know not much more about an individual other than their baptism, leaving no further traces of their existence. Kinship studies for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century communities are rare.

Several methods are available for studying the kinship of large groups. These include the use of computer simulations and oral histories. For historians, two methods are suitable for historical kinship research:

- Scholars use the patronymic indicator in areas where people inherit family names. The patronymic indicator defines the extent of a kinship network by the number of times the same family name occurs within a geographic region.

- The genealogical method involves reconstructing each family. This method requires large amounts of data covering family relations over several generations before the period under consideration.

Despite the inherent problems with the genealogical method, it is better than the patronymic indicator due to the richness of the data it is able to provide. This article uses the genealogical method to reconstruct kinship structures for Heugem.

Kinship analysis of the past

Genealogy and kinship are not quite the same. The former relates to biological connections, and the latter focuses on social relationships. Birth, death and marriage information in isolation is not sufficient to recreate kinship networks. We require additional data to assess the strength of ties and draw meaningful conclusions about kinship networks of the past.

To understand the commonalities between genealogy and kinship, historians generally use overlapping sources. A conceptual problem with the genealogical method to research kinship outside of the households is that the data provides no direct information on the social significance of the kin relations that it describes.

Within the context of the southern Netherlands in the eighteenth century, Catholic parish registers can provide this context because the priests prepared these to monitor kinship and prevent marriages that require a dispensation.

The strength of ties within the eighteenth-century Catholic framework is, given the system of marriage impediments, related to the level of consanguinity, i.e. the number of genes shared between individuals. The strength of ties is presumably greater for relatives who act as godparents, given the role they play in the upbringing of the child. However, as no ego documents exist from the inhabitants of Heugem, we can only draw limited conclusions about the strength of kinship ties.

Researching Kinship in Heugem

Family history is, in most cases, a narrative with a linear timeline, working from the past to the present. Kinship studies are a snapshot in time. Herein lays the main difference between social science and historiography: social scientists are primarily interested in developing theories to describe contemporary society, while historians seek to theorise about societal developments over time. The data presented in this paper offers a snapshot in time of the social relationships within the township.

The town of Heugem is ideal for this study because of the availability of detailed sources its small size. Primary sources used in this research include the 1796 census administered on behalf of the French occupiers and local parish records prepared by the local priest. Birth, death and marriage records from the local parish church, as well as post-1796 civil registry death certificates provided information about genealogical relationships. Two secondary sources provided information before 1734 and other towns.

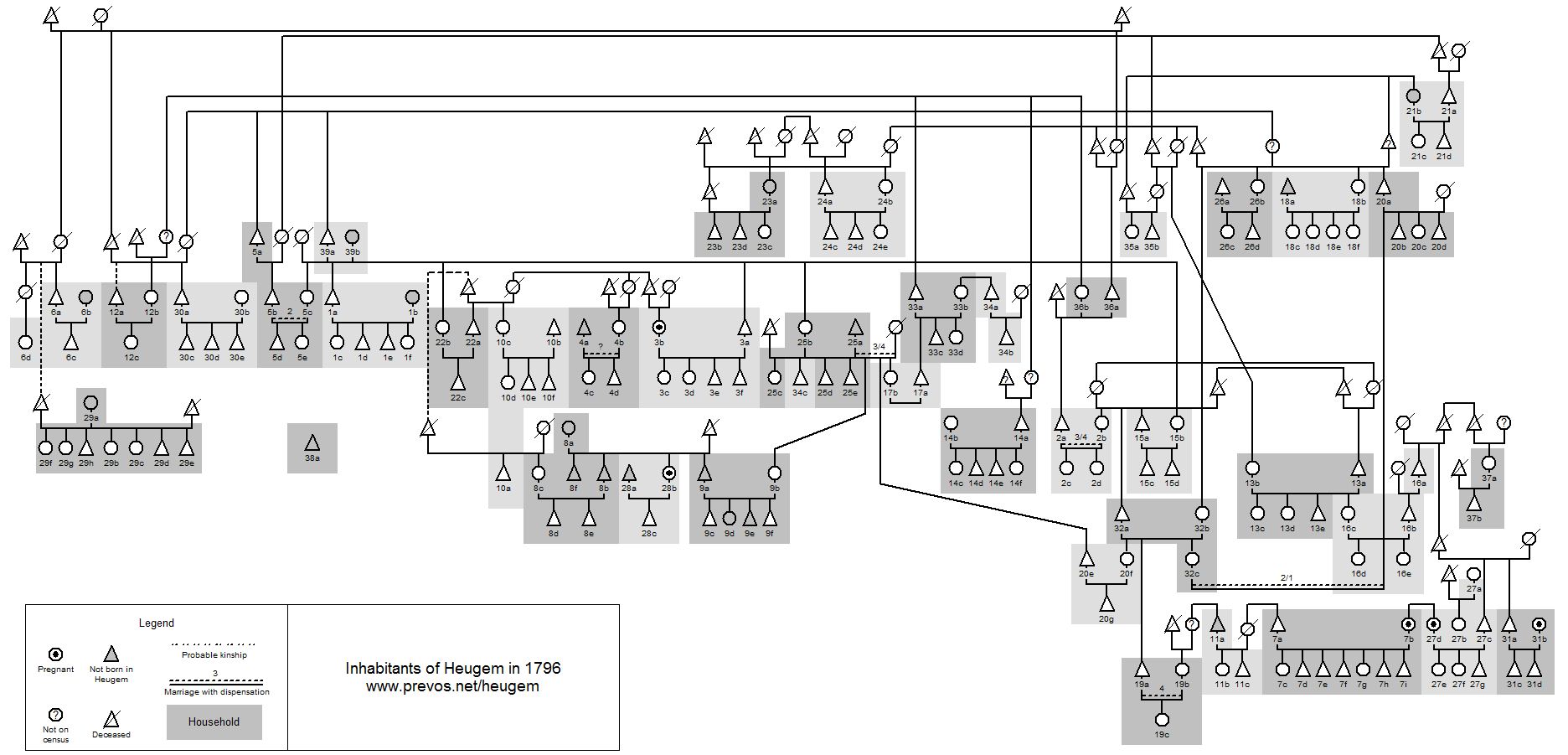

The census data is inaccurate and was corrected with information from the parish records and civil administration post-1796. The original census lists 153 people, while genealogical research indicates that this number should be at least 173. There are also several families not listed on the census, although they were born in Heugem and died in Heugem. Nor were they mentioned in the census of neighbouring towns. This research only investigates the 39 households listed on the original census.

Kinship Analysis Results

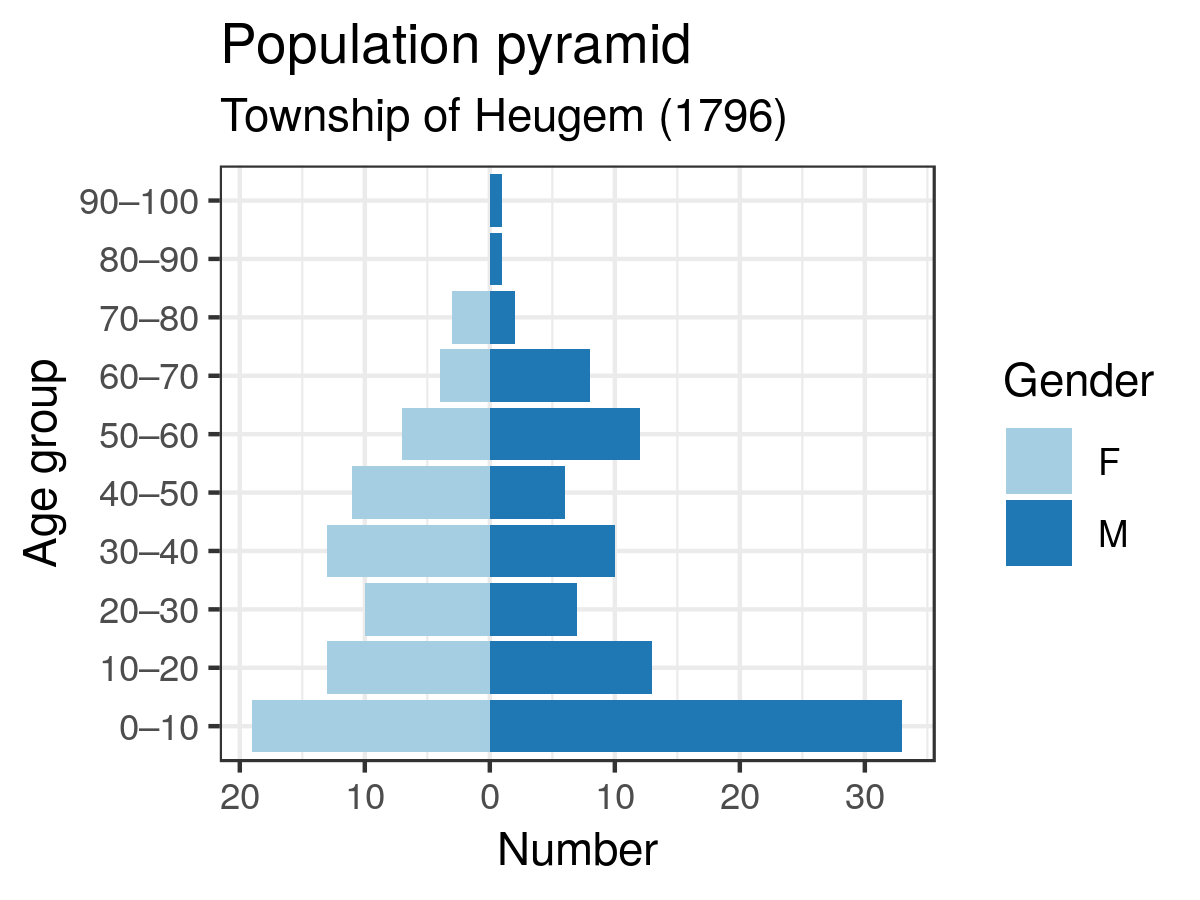

At the time of the census, Heugem had at least 173 inhabitants in 39 households, of which 53% were males. Only one household counts one person (the local priest), and there are two households with nine people. On average, Heugem counted 4.4 people per household. The average age in Heugem was 30.0 years, with the priest as the oldest inhabitant at 95. The youngest person was only two weeks old, and six women were pregnant at the time of the census.

The age distribution in Heugem shows a growing population with a stage-1 demographic transition, which is common in pre-industrial societies. Mortality among the children of Heugem was low. All but one of the children present during the census reached adulthood. Heugem was on the verge of a population explosion caused by an increased birth rate, reduced infant mortality and the industrialisation of Maastricht.

The majority (89%) of the inhabitants were born in Heugem, and 90% of the people living in Heugem would also die there. All the inhabitants not born in Heugem came from towns within a 30km radius, with only very few people from the neighbouring village of Gronsveld. Marriage patterns within Heugem were thus predominately endogamous: people married within the known confounds of their community.

A large section of the population was listed as market farmers or had related professions. The village was reasonably self-sufficient; there were blacksmiths, cobblers, a baker, a carpenter and a brandy distiller. The town also had a mayor, a teacher and a priest with his sexton.

Cohabitation Patterns

Of the 39 households identified in the census, 24 were nuclear families, and three families consisted of single parents caring for children. Three married couples were living together without children, two of whom had children living in other households.

Four households were combinations of two families. The reasons for this cohabitation were most likely related to increasing the possibility of pooling wages and labour, thus reducing the likelihood of individual poverty. Although other research has disputer economic utility as a mechanism for household formation, the data from Heugem indicates that in one of the four combined families, poverty could have driven cohabitation. For the other three combined families, the relationship between the household members is not entirely clear due to gaps in the available data.

Kinship in Heugem

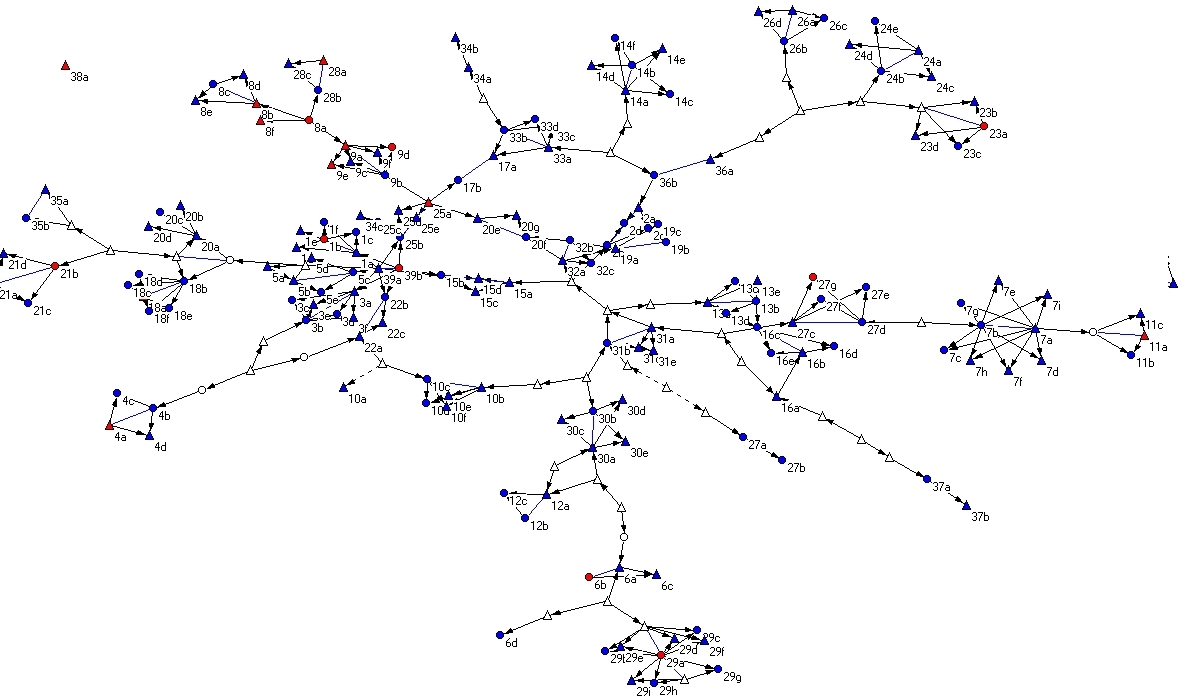

The inhabitants of Heugem are related to a very high degree, with some people having 32 direct kin relationships within the town, which means that 18% of the inhabitants were their immediate relatives. When including affinity, almost everybody could is related to somebody else in town through a string of kin relations. For example, Petrus Custers (House 7) was the brother-in-law of the grandson of the grandfather of the son-in-law of Elisabeth Coston (House 13).

With 173 inhabitants in Heugem, there are 29,756 possible reciprocal relationships. Of these possible relationships, 2,158 (7.3%) were realised. This includes 194 parent/child relationships, 356 sibling relationships, 58 grandparent/grandchild relationships, 265 uncles/aunts/nieces/nephew relationships and 786 cousin relationships. On average, each person in Heugem had a relationship with 12 other inhabitants (7% of the population). The highest number of relatives for one inhabitant was 33, with only the priest having no consanguineous relationships within the village.

Because everybody in Heugem was baptised, ritual kinship was ubiquitous. The person with the most spiritual relationships in town was the priest, Hubertus van Bloer. He baptised every inhabitant born in Heugem after 1734 and was thus ritually related to 141 inhabitants and their living parents. Although the priest seems to be a lonely figure in the village when looking at the genealogical network, through ritual kinship, he was the most connected person in town.

Marriages between relatives

Given the high level of interrelatedness between the inhabitants of Heugem, it is surprising to see that only six marriages received a dispensation.

The marriage with the highest level of dispensation was mixed dispensation in the first and second degree of blood relation. Wilhelmus Bessems married the granddaughter of his mother and her first husband. One marriage was between cousins and the other dispensations related to third- and fourth-degree relationships.

One interesting entry in the records is the burial of Nicolaus Beckers, son of first-degree cousins Nicolaus and Anna Maria Beckers. The priest notes that he was born without a mind (amens à navitate). Could his situation be the result of a birth defect due to the close relationship of the parents?

The Kinship network of Heugem in 1796

Following from this information, we can create the kinship network of Heugem. This diagram was created with the Pajek software package. Each line is a relationship between two people. Dotted lines are possible relationships.

Share this content