The Reason for Daylight Savings: Blessing or a Nuisance?

Peter Prevos |

1243 words | 6 minutes

Share this content

Moving the clock an hour forward is an excellent day of the year because we can enjoy more daylight. Instead of sleeping through the first hours of morning light, I wake up close to when the sun rises, allowing me to get most out of my day. This blissful state unfortunately only lasts for about six months as the clocks eventually are moved back again. This article discusses the reason for daylight savings time.

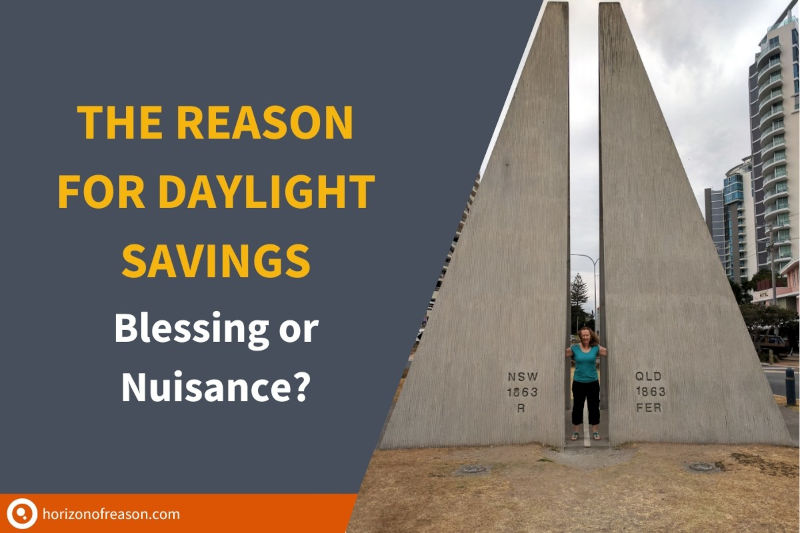

I am writing this article from Coolangatta, on the border between New South Wales and Queensland in Australia. The border runs through the middle of the built-up area. There is no real indication which part of the street is in which state. Queensland does not observe daylight-saving. This means that there is a one-hour time difference between the two sides of the road.

Crossing the street is like travelling backwards and forwards in time, without having to worry about time travel paradoxes. You can safely kill your grandfather without vanishing into thin air. In Coolangatta and Tweed Heads you can even be in two time zones at the same time, without being ripped apart by temporal tidal forces.

Daylights saving time is a controversial subject. This article discusses some of the reasons that people love daylight saving and some of the arguments against the bi-annual time shift.

The Reason for Savings

Daylight saving time makes perfect rational sense for an urbanised population at a fair distance from the equator. Why would anyone want to sleep through the first hours of daylight during summer?

The original argument for daylight saving was to save energy because people would spend less time in the dark and require less illumination. If there is more sunlight at the end of the day, there will be less time we are awake when it is dark. Although that might be logically correct, there are so many other factors that influence energy consumption that the effect of daylight saving is minimal. Also, the cost of illumination is now so small that it hardly matters anymore.

The best reason for daylight saving is that sunlight benefits your health, even when you are indoors. Natural light positively impacts our mood and has been shown to improve performance. Spending the first hours of daylight in bed thus seems to be an awful waste. In an industrial society where most people spend their time indoors, it makes perfect sense to maximise the amount of daylight they can use.

The Unreason for Daylight Savings

Some people struggle with the concept of changing time zones during the warmer months. There are reports of people that report suffering from jetlag due to the time change.

There are, however, also individuals who struggle intellectually with the concept of time changes. Some people believe that the very act of moving the clock an hour forward implies that we are adding an hour of daylight to the day. They appear to believe that changing the reference point of our clocks somehow influences the rotation of the earth.

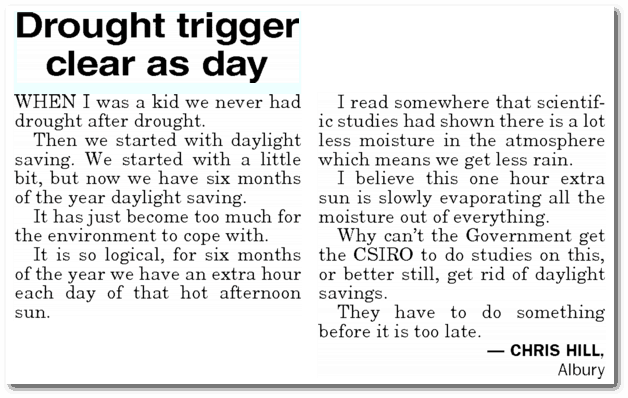

The letter shown below was published in a regional newspaper during the height of the Millennium Drought in southern Australia. The author blames the dire situation on daylight saving. He claims that the extra hour of sunlight is "slowly evaporating the moisture". Evaporation indeed increases in summer, but changing the clocks is not most certainly not causing the drought.

Daylight saving time does have negative effects because many people sleep an hour less on the day of change. This reduced sleep can lead to increased accidents, lowering productivity. Perhaps to break the ongoing discussion by changing the way we measure time.

Measuring Time

Coolangatta and Tweed Heads illustrate that time is relative. Not only in the physical sense of Einstein's special theory of relativity, but also in the social sense. The time of day is not the result of scientific research but is agreed by social convention. Time is whatever we decide it to be so that we can have a functioning society where people can do things simultaneously.

Our clock is defined by 24 hours in a day, divided by noon. Each hour has sixty minutes, each of which has sixty seconds. This system might seem strange as it would make more sense to have two times ten hour days with 100 minutes per hour and 100 seconds per minute.

The clock with two periods of twelve hours has its roots in the sexagesimal number system used by the Sumerians five thousand years ago. This system uses sixty digits instead of our system based on ten digits. The Sumerians used this method because sixty is divisible by many numbers, which helps with accurate calculations without decimals. We have inherited this number system in the way we measure trigonometry and time. It is incredible to realise that the way we measure time has not changed much in five thousand years!

Solar time

In the Roman Empire, time was based on [sunset and sunrise][6], measured with a sundial. The day was divided into twelve hours, which meant that the length of an hour varied over the course of a year, depending on your location within the empire. At the Forum Romanum, an hour was about 45 minutes in winter and 75 minutes during summer. Further north, near Hadrian's wall, an hour was between 35 and 85 minutes.

With the invention of mechanical clocks, the day became divided into 24 hours of equal length. Hours of equal length are easier to comprehend, but the downside is that the times for sunrise and sunset are always changing.

Before official time zones existed, each village kept its own time with minor differences between them. The official time was whatever was displayed on the local church clock, with noon defined by the highest position of the sun. This system worked fine for centuries, but with the invention of instant communication, it became necessary to synchronise the clocks around the country and formal time zones came into existence.

Local unofficial time zones still exist in Australia. The hamlets of Cocklebiddy, Madura, Eucla and Border Village in the east of the state of West Australia use their own time zone.

They keep their own unofficial time to stay closer to the timezone of their South Australian neighbours. The sun in that part of the state rises almost a full hour earlier than in their capital Perth.

A similar situation occurs in Coolangatta. When New South Wales changes to daylight savings, the town of Tweed Heads sticks to winter time to avoid cross-border confusion.

A new way to measure time?

Perhaps we can use technology to solve the daylight saving time problem. The way we measure time during the day has changed once before; maybe we should change it again.

We could develop electronic clocks that synchronise sunrise to always occur at six or seven in the morning. The time between successive sunrises then defines the 24-hour day. This new system provides daylight saving every day of the year, with only a gradual daily change each day.

Implementing this method would be a gigantic task which dwarfs the issues we had with the Millennium Bug. Perhaps it is time to modify the way we measure time for a third time in the past five thousand years to maximise our daylight, aided by technology.

Share this content