The Praise of Folly: The Philosophy of Carnaval in Limburg

Peter Prevos |

1362 words | 7 minutes

Share this content

Six weeks before Easter, the annual Carnaval erupts in the southern Netherlands and many other places worldwide. The yearly Carnaval is in the southern parts of the Netherlands and has played an essential role in the first thirty years of my life. When I was little, my parents took me to many Carnaval parades and parties, and the three days of Carnaval became the highlight of the year. In my second year of university, I even had the honour of being known as Prince Peter I of the Klotsköp Council of Eleven.

Many people worldwide celebrate some form of Carnaval, or Mardi Gras as it is known in some places. This essay will stick to the Dutch word Carnaval to distinguish it from other expressions of this celebration.

While at the surface, Carnaval looks like an excuse to party, be silly, dance and get drunk, this article reveals a deeper meaning behind these festivities. On closer inspection, Carnaval has a psychological function in a postmodern consumer society. Carnaval is a praise of folly and symbolises a reversal of civic society to a brief time of foolishness.

Having been away from my hometown for more than twenty years, I have obtained some distance from these traditions to place them in some philosophical context. This essay delves into the philosophical underpinnings of Carnaval in Limburg.

Origins of the Carnaval Limburg

Ash Wednesday marks the end of the annual Carnaval in many places worldwide, including my hometown of Hoensbroek in Dutch Limburg. Traditionally, Ash Wednesday marks the start of Lent, and Carnaval provides the last three joyful days before the sombre time of fasting until Easter.

The religious significance of Carnaval as a preparation for a ritualistic fast has waned over the past decades, but that does not mean that it is only about mindless partying. Carnaval plays an integral part in contemporary culture as it acts as a vehicle for meaning.

Scholars often place the origins of this festival in ancient origins and relate it with Roman Saturnalia and similar pagan festivals. However, these presumed ancient sources of Carnaval cannot be historically justified. The starting point of Carnaval as we know it today must be sought in the late Middle Ages when, six weeks before Easter, Christians celebrated 'Shrove Tuesday'.

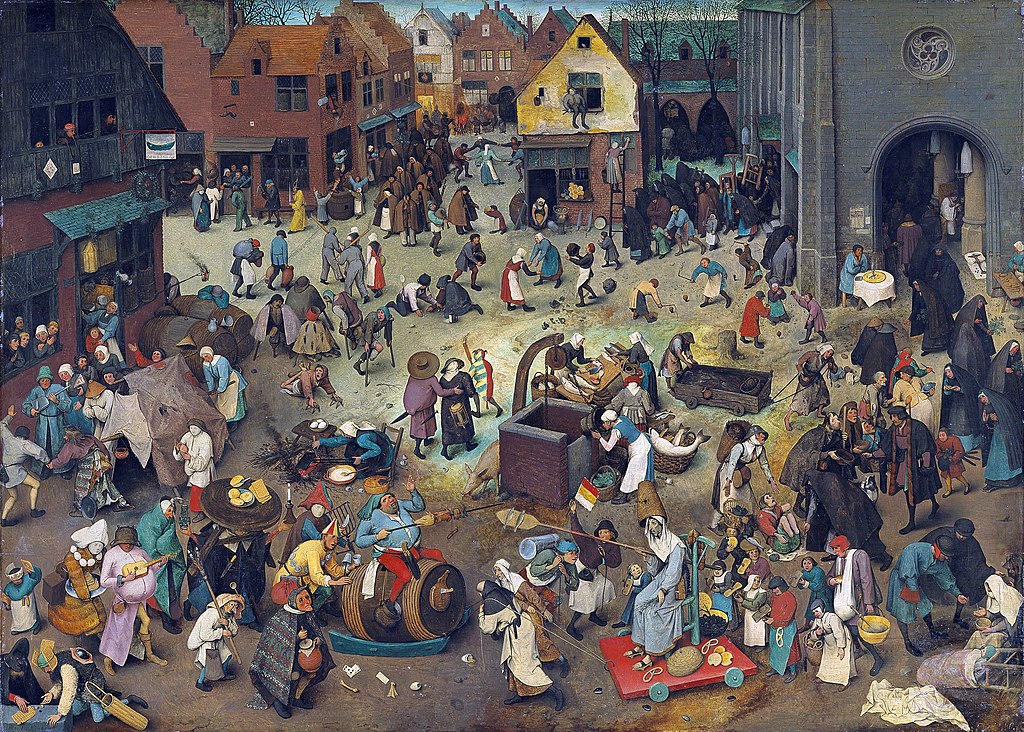

Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicts the Carnaval in his The Fight Between Carnaval and Lent from 1559. At the bottom of this painting, we see the Prince of the Carnaval sitting on a beer barrel surrounded by festivities. To his right, the serene fast is depicted, drawn as a monk and a nun, representing the religious character of this festival.

Carnaval traditions in the Netherlands can be divided into Rhenish and Burgundian variants. In the provinces of North Brabant and parts of Zeeland, people celebrate mainly the Burgundian variant of the Carnaval. The rest of the southern Netherlands is more embedded in the Rhineland traditions.

In the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg, public life is suspended for a few days, and society revolves around Carnaval. While many old traditions are swallowed up by a unifying capitalist culture, the Carnaval continues to grow.

The Philosophy of Carnaval in Limburg

Unfortunately, little is known about the origins of Carnaval. The only sources at our disposal are mainly disapproving descriptions by religious and secular rulers. The current ritualistic framework of Carnaval in Limburg originated in the German Rhineland in the nineteenth century.

Carnaval consists of three days where revellers distance themselves from the everyday rational world and replace it with the riotous non-rational. Thus, Carnaval is the ultimate expression of the Horizon of Reason.

Carnaval in the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg is highly ritualised. In some towns, worldly power is symbolically handed over to the Prince of the celebration and his Council of Eleven. This ritual symbolically moves the city out of the everyday rational world and into the world of Carnaval.

The eleven members of the council form the organising committee of the festivities. The number eleven and its multipliers 22, 33 and so on symbolise the fool. The council and the Prince are cultural mediators of the festivities, creating a connection between the everyday world of the sane and the world of the insane. The Council of Eleven is steeped in symbolism.

Their bicorne hat is inspired by the traditional garb of the jester and symbolises the foolishness central to the Carnaval. Their formal suits are a reminder of the worldly connection of the council, who are thus mediating between the two worlds. Every council member and the Prince wears a chain that symbolises their unity. The regalia of the Prince, his sceptre, pheasant feathers and other distinguishing features express his symbolic power over the three days of folly.

The most recognisable aspect of Carnaval in most cultures worldwide are the costumes worn by the revellers. Participants replace their everyday identity with a temporary one, usually signifying a connection with the bizarre world of insanity. The outfit is a mask behind which revellers can hide themselves to celebrate Carnaval without shame. Although the mask hides the revellers, it expresses their individuality. People take great care in choosing their temporary identity. A Carnaval costume is not about impersonating somebody but a more surreal expression.

The temporary loss of personal identity expresses a longing for a pre-modern time. Celebrations have a solid collectivist character, which is contrary to the highly individualised contemporary world.

This description shows a paradox in Carnaval. On the one hand, we celebrate our individuality through costumes, and on the other hand, we seek collectivist experiences. In contemporary society, personal identity is a product of individual development, and we can choose our identity. This freedom is, however, a recent development. Our identities used to be determined by tradition and heritage with limited personal choice. Although we can never fully relinquish our tradition and heritage, we now have tremendous freedom in defining ourselves. During Carnaval, the idea of a fixed identity is implicitly criticised. Our postmodern concept of individualism is taken to the extreme with the mask as a symbol of the fluidity of our identity.

Many towns organise strange, surreal activities that are totally deprived of meaning. One example is the annual Kowrenne (running of the cows), a bovine ballet that scoffs at sense and celebrates the nonsensical. This is a game whereby people run underneath homemade models of cows. There is no reason for this activity, nor does it symbolise something outside the event itself. These events are an act of surrealism that celebrates the archetype of the fool.

Carnaval is an expression of Huizinga's Homo Ludens, the playing human, resisting the individualist aspects of contemporary life by organising a collective experience. The absurdity of Carnaval is an ode to folly, with the fool as the central symbol of power, mediated by the Council of Eleven.

Carnaval is humanity's playtime, a collective defiance of the solitary self. It's a satirical salute to the folly that underpins our existence, with the fool reigning supreme in a kingdom of quirks. It's a philosophical frolic, a nod to Foucault's musings on the dance of sanity and madness and Camus' confrontation with the irrational—a ritualistic release from the rigours of reality.

Expressions of absurdity are not limited to places where the Carnaval is formally celebrated. Many sports events, dance parties and pop festivals show similar aspects. This indicates, as Barbara Ehrenreich beautifully outlined in her book Collective Joy, that we have a deep need for ritualistic moments to express the absurdity of life and relieve ourselves from having to create our own identity. Carnaval shows that we should not take life too seriously and that reason and insanity are not mutually exclusive extremes but aspects we must embrace to be fully human.

I can only close this article with a special greeting, only used during Carnaval in Limburg (and parts of Germany):

Alaaf!

Share this content