Optical Illusion Architecture in Melbourne

Peter Prevos |

1331 words | 7 minutes

Share this content

Last weekend, I visited the Escher X Nendo exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher is famous for designing speculative architecture. He created paradoxical buildings where water flows uphill, and people effortlessly walk upside down. Escher's drawings are optical illusions and impossible in the real world. This impossibility does not mean that optical illusions only exist on paper. Optical illusion architecture exploits our perception to create real-life illusions in the urban space.

This article discusses three buildings in Melbourne designed by ARM Architecture that are fine examples of optical illusion architecture. The Barak Building in Carlton, the customs building in Docklands and the Southbank Theatre are fascinating reminders that the world we perceive might not be the way we think it is.

Barak Building, Carlton. Seeing Patterns in Chaos

Our brains are wired to recognise patterns in the chaos of impressions we receive from the world around us. As a result of this tendency, our interpretation of these patterns does not always correspond with reality. We look at the clouds and see animals and a rock reminds us of a face. The software in our mind that causes us to recognise these patterns where there are none is called pareidolia. Our brains are particularly prone to see faces in random patterns.

Pareidolia causes people to see Jesus in a piece of buttered toast, or a human face on the surface of Mars. This phenomenon is not a hallucination, but a necessary part of our psychology. It enables us to recognise our friends and family in a see of people or perhaps a predator hiding in the bushes.

Essentially, all images of faces are optical illusions. Even the most realistic portraits of seventeenth-century masters such as Rembrandt are not even close to a real face. When looking at these works carefully, we just see blobs of paint. Only when we view the painting from a distance, do we recognise a face.

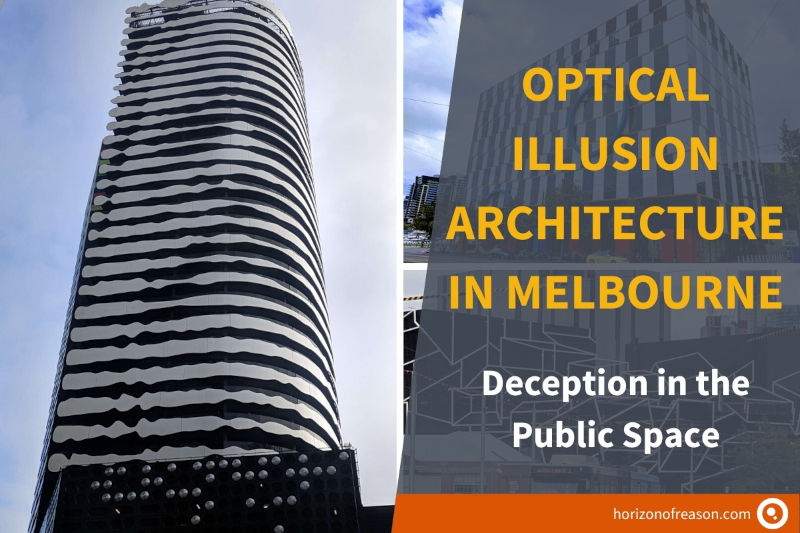

The facade of the Barak Building looks at first sight like a random set of white wavy parallel lines. Looking at this building from a distance, however, reveals a bearded face. The face that appears in these lines is an abstracted portrait of William Barak (1824–1903), who was one of the last traditional elders of the Wurundjeri people. Barak was an influential leader who fought for justice of the first inhabitants of the land that we now call Melbourne.

The location of the building is not without significance as Barak faces the Shrine of Remembrance. The shrine is a secular sacred space to commemorate the Australians that have lost their lives in war and a symbol of Australian identity. The Barak building complements this axis of remembrance by including Aboriginal culture in the identity of this country.

The face we see in this building is technically not pareidolia because it was intentionally designed to be this way. When we see the face of Jesus in a piece of buttered toast, we assume that there was no intent. The psychological principle that causes us to recognise the face of Barak is, however, the same as is the case with random patterns.

1010 La Trobe Street, Docklands: Geometrical Optical Illusions

When psychology first developed as a science in the nineteenth century, many scholars researched geometrical optical illusions. These illusions are simple drawings that deceive the senses. Lines seem bent, objects look smaller or larger than they are and shapes can be distorted.

The Café Wall illusion is a famous example of a geometrical optical illusion. In this illusion, a chequered pattern makes a straight line seem bent. The Café Wall Illusion was popularised by psychologist Richard Gregory after a member of his laboratory noticed it on the wall of in Bristol.

Docklands in Melbourne is filled with contemporary architecture in a mostly lifeless jungle of concrete, steel and glass. One building by ARM Architecture that stands out is 1010 La Trobe Street. This building was completed in 2007 and is occupied by the Australian Customs Services.

The external face of the building is decorated with black and white squares, separated by orange lines that give the illusion that the horizontal lines are wavy. In reality, these lines are perfectly parallel. This illusion is convincing and can only be broken by placing a ruler along the line.

The way the brain processes the light on the retina causes this distortion of reality. The difference in contrast between the squares and the horizontal lines causes your neurons to interpret the image as small wedges, which makes the horizontal line appear to be wavy. The Cafe Wall Illusion is only one of many examples of geometrical illusions. The existence of these deceptions shows that we can never trust our eyes when perceiving the world.

MTC Southbank Theatre, Southbank. The Ambiguity of Depth Perception

We live in what some psychologists call the ‘carpented world'. Architecture most often uses straight lines and angles to form rectangular buildings. The shapes that surround us only exist in the cultural landscape and not in nature. Because we live in this artificial world of straight lines, our brains interpret drawings in a certain way. When we see lines on a piece of paper, we might recognise these as a three-dimensional carpented space.

This perception mechanism is the ultimate form of self-deception. The image on our retina is only a two-dimensional projection of the physical world, but our mind interprets it as a three-dimensional space. Smaller objects are further away, parallel lines vanish in the horizon, are some of the interpretive schemes that exist in our mind.

Early research in psychology suggested that tribal people who don't live in the creations of Western architecture are less susceptible to geometrical optical illusions. The carpented world hypothesis states that people who reside in a manufactured environment are quicker to interpret lines as three-dimensional objects. Because our eyes are used to see carpented shapes, geometrical drawings can easily deceive our mind.

One of the great triumphs of art is the development of perspective to create the illusion of a third dimension. Artists have reverse-engineered our mind to creates the illusion of depth from a two-dimensional image. All art is therefore an optical illusion.

M.C. Escher exploited the ambiguity between two-dimensional drawings and three-dimensional objects in many of his famous works. He basically breaks the rules of perspective drawing to create his impossible worlds.

The third optical illusion building is the Southbank Theatre. The exterior of this building is decorated with a white tubular ornamental structure that contrasts with the dark building.

This building exploits our mind's propensity to interpret certain images as solid figures. The stark white lines on the facade of the theatre look like three-dimensional objects because our mind is programmed to interpret lines in this way.

This last optical illusion building blurs the boundary between two a three-dimensional perception.

Optical Illusion Architecture

These three buildings are not unique in their application of optical illusions. Trompe-l'œil, French for deceiving the eye, is a form of art that uses embraces illusions. Ancient Greek architects used optical illusions to create the impression of perfection. While columns of a temple seem to be spaced equally, the outer ones are actually a little closer than the inner columns. Architects and interior designers still use optical illusions. Forced perspective is a technique to make a room, a theatre set or whatever else seem larger or smaller than it is in reality.

In conclusion, optical illusions are not a human weakness, but a necessary part of our psychology. Our mind continually deceives itself by interpreting the light on our retina in a certain way. This deception a mental shortcut that helps us navigate the world. These three buildings are thus artistic reminders of the fickle relationship between our perception and reality.

Share this content